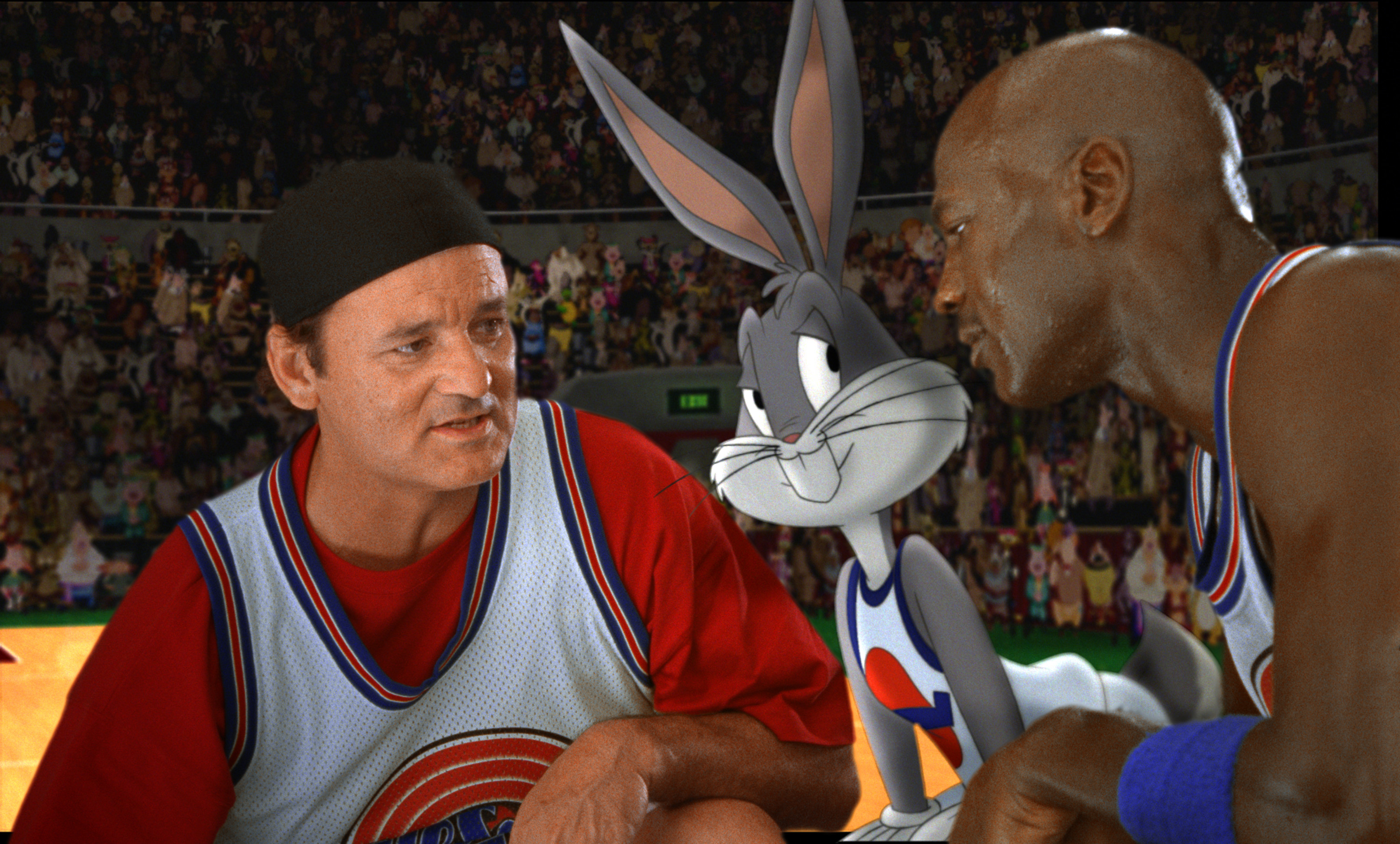

In November 1996, executives at Warner Bros. were making final preparations to release one of the most ambitious films in the studio’s 73-year history. A hybrid live-action/animated production where the fate of the galaxy depends on teaming up the most recognizable athlete on the planet (Michael Jordan) with the most popular cartoon rabbit ever put to paper (Bugs Bunny), Space Jam was an $80-million gamble for which the studio was prepared to spare no promotional expense.

Warners saw Bugs as not only a better, hipper version of Mickey Mouse, but also the most important piece of intellectual property in the studio’s film library, so the suits threw in everything they could to hype the release. Just three weeks before the premiere, Jordan himself cut the ribbon on a nine-story, 75,000-square foot studio store on Fifth Avenue. Joining His Airness at the VIP party that followed were such mid-’90s luminaries as Martha Stewart, Rosie O’Donnell, Mel Gibson and Tweety Bird. How could this movie not be a smash?

The marketing was hitting all the right notes, including on the Internet – even if no one noticed or cared. A few blocks from the flagship Warners store, up on the 29th floor of 1375 Avenue of the Americas, a group of five outcasts, working out of cramped cubicles and closets that doubled as office space, had cranked out what would become, over the next two decades, one of the most beloved websites ever made. At a time when asking to put a web address on a movie poster usually produced blank stares and then exasperated sighs, the site pushed all the limits of web development. There were inside jokes alongside animated GIFs, Easter eggs to be found and virtual reality 360s ahead of their time. It was free-flowing, unsupervised, guerrilla design work, all being done under the umbrella of one of the largest entertainment companies on the planet.

The Space Jam website didn’t exactly blow up online when it was launched, but studio execs also didn’t care. The film raked in just over $90 million by the end of its theatrical run in North America, as well as another $140 million or so overseas. It remains, to this day, the highest-grossing basketball movie ever made. Jordan and Bugs had carried the day and the site was soon forgotten, just another relic of an evolutionary moment in early web design, when code that couldn’t load fast enough through a 56K modem wasn’t code worth writing.

The site lay more-or-less dormant for the next 14 years. But that changed for good in late 2010, when the Internet, exponentially bigger than it was in 1996, rediscovered the site – almost entirely unchanged from its initial launch. It was reborn as a viral sensation, the web’s equivalent of a recently discovered cave painting. We laughed at the site because we couldn’t believe anything was ever designed this way, but also because it still existed. It remains one of the most faithful living documents of early web design that anyone can access online.

Today, the Space Jam site’s popularity has outlived almost everything to which it has been connected. The Fifth Avenue store shuttered in 2001. Both stars of the movie’s stars made forgettable exits in 2003 – Jordan with the Washington Wizards, Bugs with Looney Tunes: Back in Action. And every person directly associated with the site’s creation has now left the studio.

But the site lives on, aging for 19 years but free from influence, to our enduring delight.

The first movie website was created by MGM in October 1994 to promote the release of Stargate, the Kurt Russell/James Spader sci-fi adventure that would gross nearly $200 million worldwide, spawn several TV spinoffs and give director Roland Emmerich the juice he needed to next tackled another tentpole sci-fi film, Independence Day, which is now filming a sequel for 2016. So Stargate‘s role in modern Hollywood history is well-regarded, but its website reads like pure desperation: “Click on the pictures below to learn more about what is sure to be one of the most exciting films of the year!” The design was rudimentary, the copy uninspired, but it was a start.

Don Buckley sure noticed. As Warner Bros.’ vice president for advertising and publicity, his entire job rested on being able to reach new audiences wherever they were hiding. And as an early adopter of the web, he had an epiphany before many of his peers.

“I was on the Internet before there were graphical browsers, and it was still fascinating to me,” he says. “I spent way too many hours deep into the night exploring this netherworld. I was a movie guy and I thought, ‘Oh, wait a minute, we can do some things here, we can market movies on the Internet.’ It became as much a creative exercise as anything else, but it was this new playground that had presented itself.”

The problem was Buckley couldn’t convince his superiors to allocate much of a budget or staff to pursue this untapped area. Finally, with more prodding, management allowed him to hire a web designer away from Time Inc.’s Pathfinder portal, which mostly served to host sites for magazines like Entertainment Weekly and Sports Illustrated. Her name was Dara-Lynn Weiss, and she and Buckley helped create the site for Batman Forever in the spring of 1995, the studio’s first true movie site.

“No one had really done web development to that point,” she says. Weiss taught herself HTML and SuperBASIC, staying up all night to read programming language how-to books and scour how other websites approached design. “It was extremely onerous and painstaking, but I found it very exciting.”

And while Weiss toiled away online, Buckley fought for more resources, more attention and more respect. “Some of the people in publicity kind of considered us a pain in the ass,” he laughs. The photos he’d request for the sites were the same ones offered to newspapers and weekly magazines as exclusives. Studio execs had a hard time understanding, perhaps rightfully so, how the Internet represented any serious means to finding an audience. “I had to convince people within the studio that it was a good idea to put the website address on the poster,” Buckley says. “There was a lot of resistance to that.”

“The job was awesome, but the drawback was that no one cared what we did,” Weiss adds. “We got very little attention. My friends had no idea what I did for a living because they weren’t online yet.”

By the spring of 1996, Buckley had shown enough progress that he was permitted to hire not one but two more designers. On March 25, Jen Braun and Michael Tritter both started at Warner Bros. Online, each with a very specific skillset and background. Tritter was an angsty 26 year old who had just returned from three years in Slovakia. Armed with a politics degree from Oberlin, he was worldly and free-spirited and suspicious of authority. He loathed the idea of working for a corporate conglomerate like Warners. “My disdain,” he tells me, “was palpable.” On the other hand, Tritter needed a job, shared a mutual friend with Weiss and could write copy, and he soon warmed to Buckley’s similarly boisterous approach.

Braun, meanwhile, had grown up an hour outside of Cleveland in Massillon, Ohio (“City of Champions“) and was a rabid basketball fan from the start. As a young girl, Braun and her parents drove to the Richfield Coliseum countless times to see Cavs teams led by Mark Price, Brad Daugherty and Craig Ehlo. And when the Bulls were in town, she would make sure to bring her zoom-lens camera, scamper down near courtside and take photos of Jordan from as close as she could. She was mesmerized by his skill and athleticism. This fandom was pushed to its limits when Jordan hit The Shot in May 1989 – she cried as Ehlo crumpled in defeat – but he nonetheless held a special place in her basketball memories. The photos she’d snapped foretold a future career that depended on an artistic eye. The following year, Braun enrolled at the University of Cincinnati and majored in graphic design. Before she graduated in 1995, she created the school’s website as her senior project. She only got a B – “They never actually saw it on a computer,” she says, “only as a printout!” – but the site survived for years.

Braun created a “digital portfolio” – essentially a collection of Macromedia Director files, perhaps 2 to 3 megabytes each, loaded onto a bulky SyQuest disk – and sent out copies to potential employers in New York and San Francisco. She eventually took a position at Pathfinder, where she met Dara-Lynn Weiss. When Buckley poached Weiss, Weiss poached Braun just a couple months later.

Weiss saw the group as its “own little fiefdom,” and 2,500 miles away from Warner headquarters in California, Buckley’s online unit surely operated as if it was an independent design collective. Wednesday lunch meetings intended for brainstorming ideas would last for hours on end, and everyone pushed each other as to how their sites could stand apart from the tame approach that defined traditional marketing.

The first site they worked on, for the 1996 summer blockbuster Twister, was made to look like an old green-type computer terminal. After you “logged on,” an email warned you about a “tornado developing 30 miles east” and wondered whether you would like to be a volunteer storm chaser (Sure! Why not?) From there, you were taken to the Severe Weather Institute Research Lab (SWIRL) site and supplied with various tornado-related stats, important tornado terminology, even practical advice for what to do if you are ever caught in a tornado’s path. (“Absolutely avoid buildings with large free-span roofs. Stay away from west and south walls.”) Even the wallpaper was dotted with rain clouds poking out little lightning bolts. Buckley’s team wasn’t interested in theater times and plot synopses; their sites were meant to be fully formed online experiences.

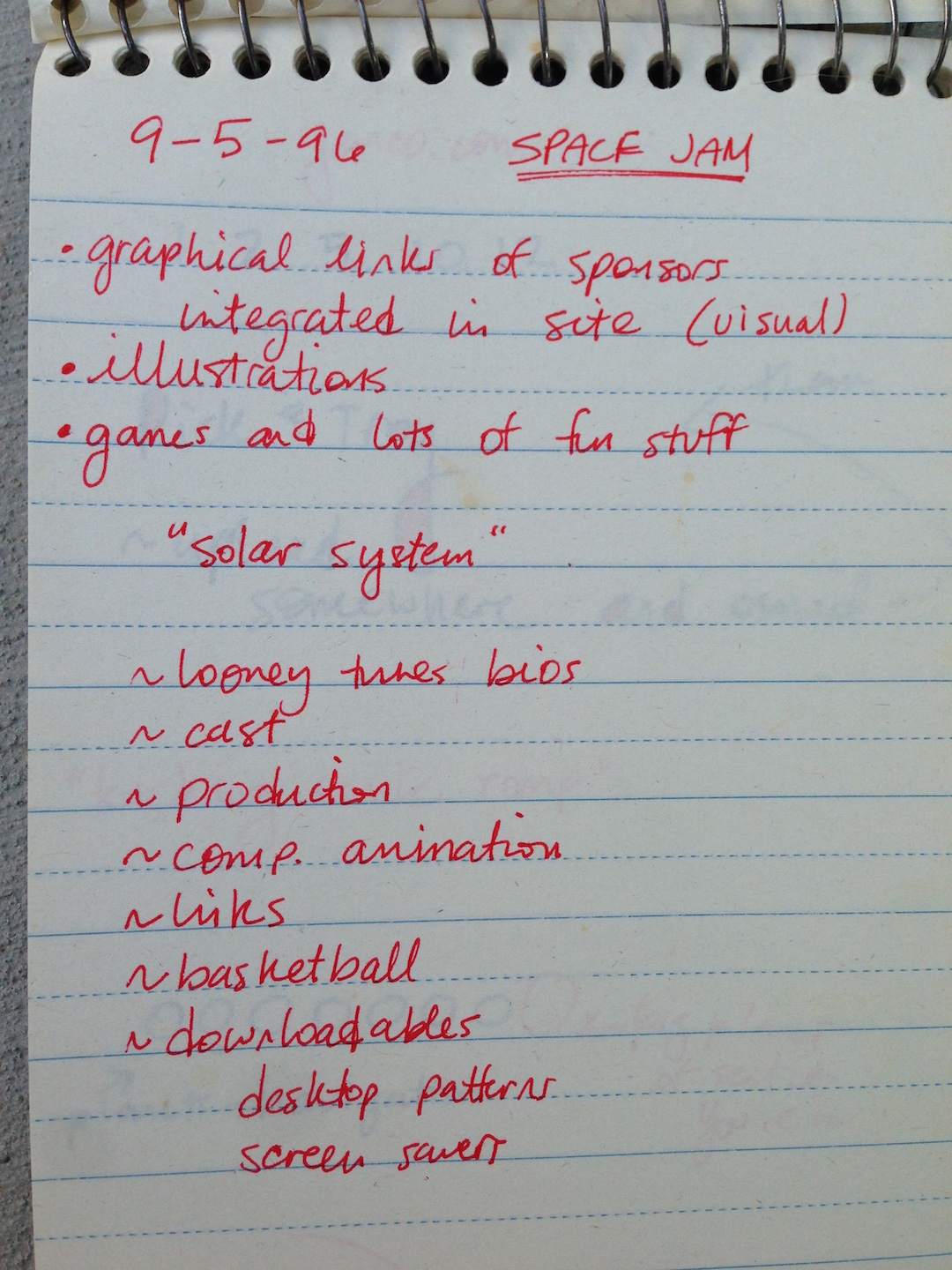

By that fall, Buckley’s crew was a fully operational, smooth-running gaggle of coding revolutionaries. Their office bible wasn’t the notes they received from Warner Bros.’ consumer products division but rather Teach Yourself Web Publishing with HTML in 14 Days, an indispensable 800-page beast of a book that became more tattered and dog-eared as time went on. (Tritter still has his personal copy on his home office bookshelf.) They had mastered the basics, Twister had fostered their creative spirit, and once Braun hired her fall design intern, a University of Cincinnati undergrad named Andrew Stachler, the core team was now assembled and ready to tackle its most ambitious project to date: Space Jam.

To hype the site, Braun and Tritter designed a placeholder site, done up in the style of an old subway station, with Space Jam movie posters adorning the background and a subway car full of Looney Tunes characters. It proved to be exceedingly difficult to execute – “a nightmare,” Tritter remembers – with its meticulously coded tables and pixel spacers. Alas, the placeholder page has been lost to history.

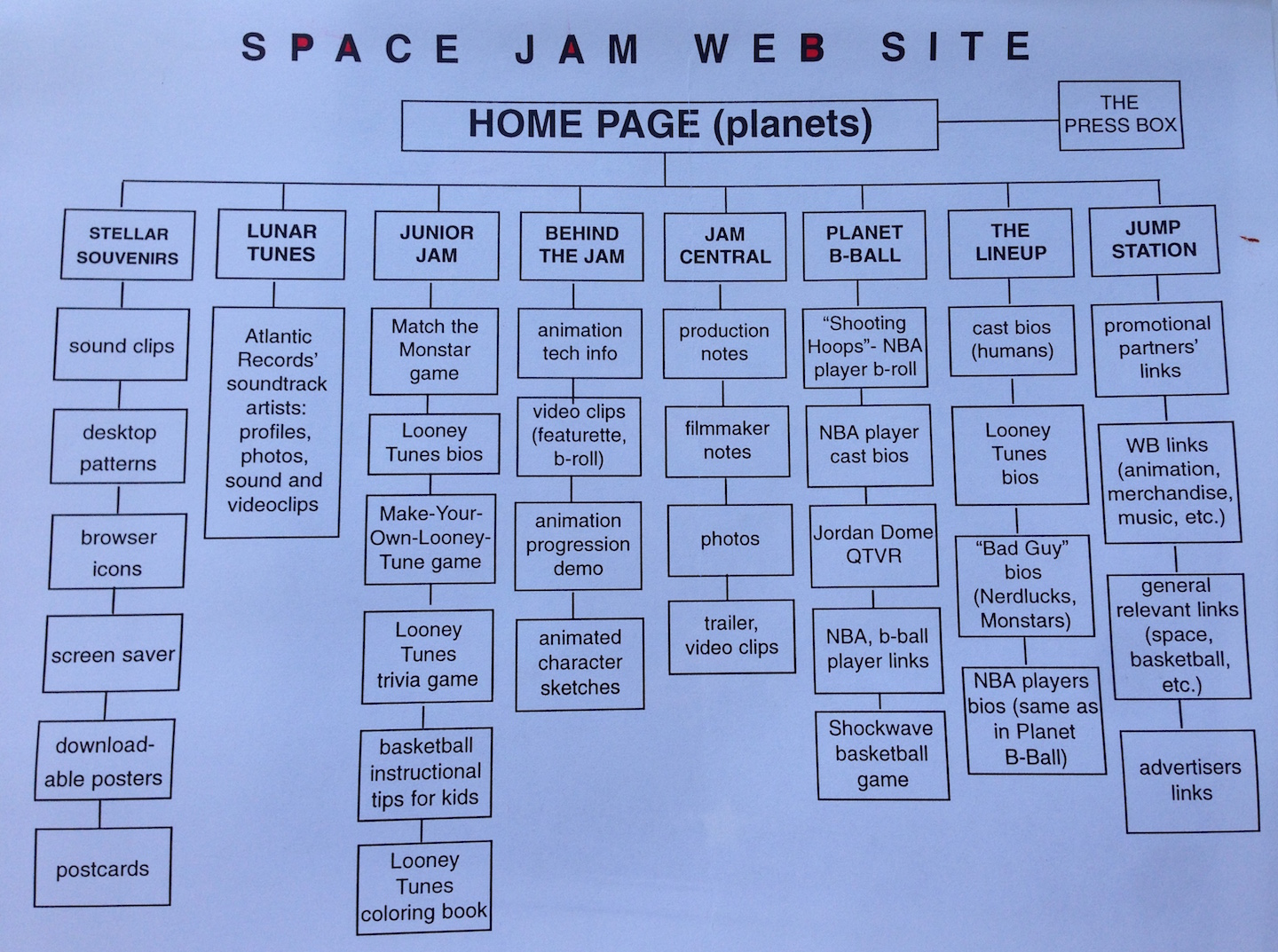

But the rest of the actual Space Jam site, which is what you see today, was a more gratifying experience for Buckley’s team. The opening galaxy of icons is both minimalist and cartoonish but with functional site section names: Jam Central for movie facts and filmmaker bios, Lunar Tunes for soundtrack info, Stellar Souvenirs for sound clips and screen savers, and so on. Even today, with its basic HTML, pre-broadband file sizes, and Flash-free architecture, the site is easy to navigate, even on a mobile phone. The movie clips, encoded in QuickTime, are somewhat grainy but still viewable. Nothing was designed to still work after 19 years; it was simply designed to work.

“I didn’t think it was limiting,” Braun says. “I liked to find creative solutions. We used 1-pixel blank GIFs everywhere and stretched them. We found really creative ways to make things look the way we wanted. There’s so much technology out there now, but I still write HTML where, if you don’t have a style sheet, the page will still work. I still try to keep to the core values.”

Braun and Stachler handled the design, while Tritter and Weiss wrote much of the copy, which is arguably the funniest component of the site as it still exists. To read some of the wording that made it to the site is to become convinced that Buckley’s team was subject to minimal oversight and even less corporate interference. According to Buckley, the approvals process back then amounted to this: “Yeah, that looks good, let’s launch.”

The site’s tone has a casual feel that borders on nonchalance, the kind of indifferent attitude that younger teens might embrace:

Here you’ve got footage taken from additional cameras on the set (and called “b-roll” by those in the biz) in which Michael Jordan plays against several men who are both shorter than he and less talented at the sport of basketball. The little green men will later be digitally removed and replaced with cartoons. Neat stuff, huh.

Learn how megastar Michael Jordan got a big kiss from classic wisecracking hero Bugs Bunny! Watch as Michael Jordan plays basketball against many strange men in green suits and facemasks – who never appear in the film!

If these jaded descriptions sound like they were written by someone with zero interest in the NBA and a slightly subversive worldview, that was Tritter in 1996. “I knew nothing about any sports, especially basketball,” he confesses. “The irony now is that now I have an 8 year old who only wants to talk about basketball.”

Tritter’s wry wit also shows up embedded within the source code of many of the site’s pages, still very much visible today if you know where to look (“Model Rocketry is fun and educational,” “Go ahead and jump. Might as well jump,” “Oy, am I tired”). Sans context, they seem like a hodgepodge of pop-culture references and nonsensical ramblings, but it was Tritter’s way to keep the overwhelming monotony of coding at bay and, at the same time, put a little of his personality on display.

“You can tell what music I was listening to that day or what books I was reading,” he says. “It was just jokes to myself that no one would ever see – and it was a way of keeping myself sane – but I guess they ended up being seen.”

But what was seen, more than anything, was Braun’s design. Working from a top-of-the-line Apple Macintosh and using BBEdit to code, DeBabelizer to compress and shrink JPGs and GIFs, and Photoshop and Illustrator to create design elements – all programs still very much in use today – Braun helped bring a cinematic world to life. And though today’s standards may only enhance its apparent simplicity, the site is, in many ways, a technical marvel. Years before virtual reality became chic, the team went out West and created a 360-degree tour of the “Jordan Dome” – the practice enclosure/basketball court built on the Warner Bros. lot to capture the NBA stars’ footage – by setting up a tripod during off-hours, capturing images every 15 degrees and then stitching them together into a QuickTime VR file. There was a “coloring book” with downloadable black-and-white sketches, and a 5,000-word section on the various technologies that helped make the movie. There was an online quiz before online quizzes were popular, and all of the WAV, AIFF and QuickTime files are still functional and ready for download. (There are also some undiscovered Easter eggs the team is reluctant to disclose, even two decades later.)

If Warner Bros. bigwigs were happy with the site, which went live a few weeks before the movie opened, the team never knew.

“Nobody gave a shit,” Tritter says, “and that waxed and waned over the years. At first, we could do whatever we wanted, then all of a sudden, people thought, ‘Oh wait, this is really important, we should pay attention to it, even though we have no idea what we’re talking about.’”

But for a while, he adds, “we could do whatever we wanted.”

Buckley’s team kept pushing beyond what anyone expected because there was no one to tell them otherwise. In 1997, Batman & Robin (as if it could possibly be associated with any more regret) boasted the first movie site fully built using this newly rebranded graphics animation program called Flash. “At the time,” Braun says, “we had a lot of people coming to us saying, ‘Can you please use our technology because then it will become something?’”

“We were always trying to push those creative boundaries,” Stachler adds. “If you’re going to get someone off the sofa to see a movie, you have to show them something that they’ve never seen before.”

But Space Jam, which was certainly unlike anything moviegoers had seen before, came and went. And at some point in 2003, the studio redirected the original URL (www.spacejam.com) to a scaled-down site designed solely to sell special-edition DVDs of the film. So as far as anyone could tell, the original Space Jam site – one of the most original and cutting-edge examples of nascent web design – was gone.

Jen Braun remembers very well the day that she became an Internet sensation. It was December 29, 2010, and she was home visiting her parents in Ohio. She had left Warner Bros. in 1999 and eventually moved to Spain for a decade, all the while continuing to do design work, but she was back stateside for a brief spell. Two days before the New Year, someone from Reddit.com had found an email address from her personal website and wrote a peculiar-sounding note. “Hey this is kind of out of the blue,” it read. “Today on a popular website called Reddit; an old site you created was brought up as a nice bit of nostalgia.” The writer went on to ask if she’d be open to conducting an Ask Me Anything on the site, which she did two days later.

Don Buckley had left the studio in 2008 and started his own marketing company. The studio stopped making its own sites back in 2001 – Ocean’s Eleven was the last one – and began outsourcing all production to outside firms. Someone from Warner Bros. passed him a link to a news story about the site’s rebirth. Soon enough, dozens of mainstream news sites had caught on. SB Nation called it “a lost treasure of the Internet.” Comics Alliance said the site was “a genuine (and genuinely garish) piece of Internet history.”

When reached by private message, the Reddit user who rediscovered the site said that it happened completely by accident. “To the best of my knowledge, I was hanging out with some friends at the time and we started talking about Space Jam and decided to look it up,” he says. “At that point we realized the site hadn’t been updated in a long time. From there I posted it to /r/TIL mostly because I wanted to see what other people said about it. I was expecting a few comments, but by no means was I expecting it to blow up like it did.”

Buckley was floored: “I had no idea it was still up.”

Same for Dara-Lynn Weiss, who left Warner Bros. in 2000 and had worked in marketing and programming at various companies: “I just assumed they had all been taken offline,” she says. “I just assumed everything expired at a certain point and then I’d never see them again. It was so funny to see what we wrote and what that homepage looked like – how dated it looks but also how much it holds up.”

Warner Bros. has always demonstrated a great reluctance to publicly discuss the Space Jam site – a source inside the studio declined to supply any current traffic stats, citing “proprietary information” – but Tritter and Stachler were both still working at the studio when the site blew up. Tritter was senior vice president of interactive marketing, while Stachler (who returned in 1998 after graduating) was his VP. Both had relocated to Los Angeles in Buckley’s stead, but the sight of that old galaxy-inspired homepage brought back memories of long days and late nights at the old Midtown office.

People inside Warners were surprised and mostly delighted, they recall, but at least one executive figured the best way to address an unwanted site that had quickly racked up, by one estimate, 500,000 page views was to shut it down. Solely because it was not a monetized asset, to use the sterile parlance of studio bean counters, the Space Jam website was dead for at least a few hours, perhaps longer.

An incensed Tritter called the person responsible and implored him to flip the site back on. “Some idiot thought, ‘Well, that’s not supposed to be there anymore and there’s all this traffic coming in,’” he recalls. “Andrew and I are like, ‘What’s wrong with you? Why would you?’” Soon enough, the site was restored, but Tritter still thinks about that very sudden death every time he sees the site. “Is someone at some point going to say, ‘Oh, I guess we should take it down now, and that’ll be it?” he wonders.

Stachler is more direct: “If we had left the company, the site probably would not exist today. It would’ve gone down for good at that time.”

Despite being a (gasp!) deeply silly and poorly directed film, Space Jam has always maintained a devout following. No other hoops-centric movie has ever grossed more in theaters. The soundtrack, featuring R. Kelly, Seal, Coolio and other ’90s staples, sold more than 6 million copies. On a more practical level, the daily workouts and scrimmages that filled in gaps between filming also helped Jordan get back into basketball shape after leaving the game to play minor league baseball. Space Jam‘s total economic impact, according to a 2009 Chicago Tribune article, has topped $5 billion.

Maybe it was folly to think that Space Jam could ever flop. You could argue that if any film didn’t need a website, it was this one. With stars such as Jordan (and other future NBA Hall of Famers like Charles Barkley, Larry Bird and Patrick Ewing) as well as an iconic cartoon character like Bugs Bunny, Warners would’ve had to commit cinematic malpractice on a legendary scale for the film not to be profitable. But around the time Space Jam was released, movie websites had finally cemented themselves as a necessary component of any big-budget release, at least according to a Chicago Sun-Times story a month after Space Jam‘s premiere. “No one knows whether the Web sites actually bring audiences to the movies or if they just entertain those who’d be seeing the movies anyway,” it read. “But anecdotal evidence shows that movie Web pages bring the kind of word-of-mouth publicity that traditional advertising can’t buy.”

It may have taken some 15 years for the Space Jam site to generate that kind of attention, but it remains a fascinating love letter to a web that only still exists within its bones. The code that makes up the Space Jam site is the same basic programming language that still comprises much of the modern web, and its design, attitude and overall aesthetic became magic captured in a bottle, immune to the myriad technological advancements that have come and gone while influencing a generation yet to come. And if not for a few self-taught web developers in just another Midtown high-rise, Space Jam might’ve spawned just another forgettable site from the web’s adolescence.

Don Buckley is still based in Manhattan; he’s now the chief marketing officer of Showtime Networks. “There’s a great deal of pride. We created something that never existed before, this new means of communicating,” he says. “Now, not to make it too lofty – we’re marketers, that’s what we do – but we found a new way to put ourselves out there.” Buckley’s kids brag about the site to their friends – “I have total cool dad cred,” he gushes – and even the twentysomething production assistants in Showtime’s Los Angeles offices have stopped him on occasion to be regaled with stories of how the site was born.

Jen Braun has also seen the stunned look of millennial faces when she confesses her involvement with Space Jam. She’s now back living in Ohio and still working on marketing and web design projects for clients. “I’m sure it will follow me, and that’s fine,” she says. “At the time, we never thought that it would live this long and have this much of an impact. There’s no way we would have ever imagined this.”

Dara-Lynn Weiss went on to become an author, entrepreneur and started her own business selling an all-weather, UV-resistant umbrella. “I think the tragedy of digital media is the rarity that you can go back and look at this stuff. So much has gotten lost,” she says. “Much of it wasn’t of great value anyway, but sometimes I feel like they should all just stay up forever. Why not? There tends to be a better record of every other medium than the web, because when it’s taken down, it’s really gone. I think the site we made is a beautiful piece of nostalgia. There’s the sad, abandoned Internet, but with Space Jam, there’s nothing about it that’s that.”

Once Andrew Stachler came back to Warner Bros. in 1998 with a college degree, he stayed for 16 more years. He left in 2014 and now works as a marketing consultant in the Los Angeles area. “It felt like we were a family making these things together,” he says of the Space Jam days. “We were just a bunch of kids figuring it out. That kind of marketing has become so much more corporate, but those were sweeter, more romantic times.”

His old boss, Michael Tritter, also left the studio in 2014, after 18 years of service. He’s now involved in various production projects around Los Angeles. He still keeps every site the team ever created in a box full of Zip disks, in case some digital media archivist comes calling. Like Braun, he knows this may be his lasting career accomplishment – “it’ll be on my fucking tombstone” – but he maintains there’s significant historical and technical value in keeping these sites alive and accessible, able to sit alongside the most tricked-out, parallax-scrolling presentation just a browser tab away.

“It’s vital that you see where things came from,” he tells me. “It’s nice to have that stuff still around, but it should just stay there. If it’s weird and funny to look at it 19 years later, think of how weird and funny it’s going to be in 30 or 40 years. There’s no reason to take it down. It just becomes more and more of an interesting artifact.” And just to make sure it never comes down again without anyone noticing, a Twitter bot (@SpaceJamCheck) has been sending out site status updates every three hours for nearly two years.

And now, almost 20 years after the original film, Warner Bros. is apparently serious about producing a Space Jam sequel, perhaps one that stars LeBron James. So here’s an idea: Get the original design team back together and do the Space Jam 2 site exactly as the first one. Enlist Braun, the lifelong Cavaliers fan, to design the site, beef up the studio server bandwidth and watch the magic happen once more.

“They would absolutely be crazy if they didn’t,” Tritter says. “I will do everything I can to make sure it happens. I don’t know how I’d be feeling if I was still there and they did that.

“I would probably lose my mind.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.