Join today’s leading executives online at the Data Summit on March 9th. Register here.

AI today (mostly) excels at narrow, specific tasks, like writing an email on a particular subject or generating an image from a caption. But it falls short of the definition of artificial general intelligence (AGI), which would be a machine capable of understanding the world as well as any human. In the 1950s, researchers including AI pioneer Herbert A. Simon were convinced that AGI would exist within the next few decades. Since then, AGI has proven to be a daunting, perhaps even impossible-to-achieve milestone. Writing in The Guardian, roboticist Alan Winfield claimed the gulf between modern computing and AGI is as wide as the gulf between current space flight and faster-than-light travel.

Still, others insist that AGI is drawing close within reach. One is Geordie Rose, who cofounded the quantum computing startup D-Wave Systems in 1999. Rose’s newest venture, Sanctuary, today announced that it raised $58.5 million in a funding round led by Bell, Evok Innovations, Export Development Canada, Magna, SE Health, Verizon Ventures, and Workday Ventures to build “the world’s first human-like intelligence in general-purpose robots.”

Rose claims that a combination of “breakthrough” technology in “AI, cognition, computer vision, machine learning, theoretical physics, and quantum computing” will help to achieve Sanctuary’s ambitious vision: robots that “mimic the different subsystems in a person’s brain” to break down work into manageable pieces. But skeptics abound, including former Salesforce chief AI scientist Richard Socher.

“Most startup succeed because they focus on a niche and then expand. Building some general AI with the right software and hardware with that amount of funding will be incredibly difficult. Likely, [Sanctuary] will eventually have to go more specific in their application, make their tech concrete, build something tangible that can be sold into one market and really solve a problem,” Socher, now the CEO of web search platform You.com, told VentureBeat via email. “That solution will probably not be AGI and a generally useful humanoid robot.”

Journey to Sanctuary

Before Sanctuary, Rose co-launched Kindred, a secretive AI company based in Vancouver, Canada, with cofounder Suzanne Gildert. Armed with funding from Google, Bloomberg Beta, and others, Rose and Gildert embarked on a mission to build robots that can learn by observing tasks that humans perform.

Gildert says she came up with the idea for Kindred while working as a physicist at D-Wave. In cases where there isn’t much data to train a robot, humans could supply training data by guiding the robot, she conjectured — letting robots do things they couldn’t on their own while simultaneously making them more capable.

The technique, sometimes called “imitation learning,” has been widely applied in the robotics domain. Researchers at Google have “taught” robots to learn how to walk by mimicking a dog’s movements, while OpenAI’s now-disbanded robotics division have helped robots grasp objects by “watching” examples.

But while imitation learning has potential, it isn’t without shortcomings. Imitation learning-trained systems don’t always generalize well to scenarios that weren’t included in the training data, and generalization issues can arise due to dataset biases even after many demonstrations. Imitation learning also assumes that humans can demonstrate the desired task, which isn’t always possible — especially where a robot has a physical advantage.

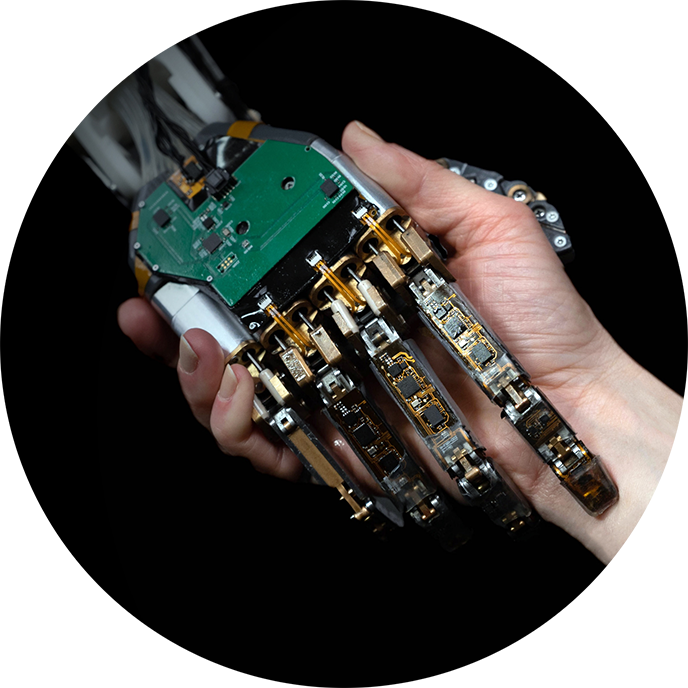

Still, Rose and Gildert asserted that Kindred’s approach to imitation learning could one day lead to “human-level AI.” In labs filled robots, Kindred employees wore virtual reality headsets to “see” what robots were seeing and use handheld controllers to help the machines pick up objects. Every time the humans helped the robots, algorithms used the data to make the machines smarter over time.

“The systems we have now are able to move from the neck up, more or less like a person. It’s not perfect but it’s close. The next step is to actuate them from the belly button up — most of the tasks that people do in their everyday lives are actually done seated,” Rose told The Globe and Mail in a September 2018 interview. “That means that we can build machines that can do the kinds of jobs that humans do cheaper, better and more effectively than people do.

At one point, Kindred’s R&D efforts included a headset-and-sensor-equipped suit that could allow humans — and even animals — to control and train an army of robots. Experts expressed skepticism that the company could deliver the system as described, and — perhaps reflecting the technical realities — Kindred eventually scaled back its ambitions. After pivoting to robotic systems that can pick, place, and sort products for ecommerce fulfillment, Kindred was acquired in November 2020 for $262 million by British supermarket Ocado, which had already invested heavily in robotic fulfillment systems.

Arriving at Sanctuary

In 2018, Kindred spun off its R&D division under the brand Sanctuary. Rose stepped down as CEO and president of Kindred to lead it, with the understanding that Sanctuary would license some of Kindred’s patents and software and maintain a minority ownership.

Rose describes Sanctuary’s work as a continuation of the early research at Kindred: understanding the human mind well enough to build one in a machine. He envisions human-piloted or human-supervised robots that can perform virtually any task, from clearing a landmine to sterilizing a hospital to exploring outer space — robots that can think, reason, and interact with the world like a person.

“What if you were not limited to having access to just one human-like mind?,” Rose muses in a blog post published this morning. “Machines that could work like this will become a vital part of solving all kinds of complex problems. But it’s not just forward-looking use cases. These machines could also be used in the near term to perform tasks that are too dangerous for people.”

Rose’s grandiose plan is to build machines that share the same values — and even the same rights — as humans. During a talk at McMaster University in 2018, he said that he aspires to one day establish a sanctuary city in Vancouver where robots of the future would live and work alongside humans.

“[Robots] will be able to understand the world the way we do, have the same emotional spectrum, have the same feelings of self,” he said at McMaster’s 33rd annual J.W. Hodgins Engineering Memorial Lecture in Hamilton, Ontario. “We can’t do it yet but as a north star, it guides the work I do.”

Rose says that Sanctuary has interest from customers “representing a dozen different industry verticals,” and Sanctuary’s advisory board includes former astronaut and commander of the International Space Station Chris Hadfield and Anousheh Ansari, the first self-funded woman to fly to the International Space Station. Market momentum would appear to be on Sanctuary’s side, too, with ABI Research predicting that the market for mobile robotics — such as the automated guided trailers used in warehouses — will grow 47% a year to 2.4 million units in 2025.

“With unfilled vacancies, workplace safety considerations, increasing employee turnover, worldwide aging populations, and declining workplace participation, one thing is clear: many labor-related challenges are outside the scope of current specialized AI and robotics technology,” Rose told VentureBeat via email. “The advent of a general-purpose, human-like technology like ours will fundamentally change the nature of our relationship to technology and our connection to the world around us.”

But AI researchers and roboticists to VentureBeat spoke to characterize Sanctuary’s vision as far-fetched.

“There doesn’t seem to be anything new from a technology standpoint here. They’re definitely overhyping what would seem to just be a pretty standard reinforcement learning (RL) robotics startup,” Matthew Guzdial, a University of Alberta assistant professor focusing on machine learning, said via email. “They do have the relevant expertise with Gildert, but the vision they put forth is overblown. People like Ayanna Howard, Andrea Thomaz, Sonia Chernova, and more have been working to try to create general-purpose robots like this with the same technology for decades. It’s really hard! And nothing that they’ve shared here suggests any sort of technological breakthrough to make it easier.”

When contacted for comment, Rodney Brooks, a professor of robotics at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab, said he couldn’t find anything coherent enough on Sanctuary’s website to evaluate. (Sanctuary declined to provide details about its technology beyond what’s been made public.) And Socher noted that, even if Sanctuary can deliver on its lofty promises, creating a more human-like robot might not necessarily be desirable, given that robots can be more special-purpose than humans (think a dishwasher versus a robot hand washing dishes like a human).

“It’s hard to criticize the mission, both because it’s an inspiring long-term vision but also because it’s so light and fuzzy on the details in the short term,” Socher added.

The current landscape

Rose joins the cohort of entrepreneurs and researchers who’ve promised — and not yet delivered — AGI in robot form. Last August during a press conference, SpaceX and Tesla CEO Elon Musk similarly touted a general-purpose, robot humanoid — dubbed Tesla Bot — designed to perform “dangerous, repetitive, and boring” tasks like providing manufacturing assistance.

But countless AGI efforts have failed to bear fruit. A team led by Israeli neuroscientist Henry Markram, who promised to reverse-engineer the human brain by 2019, abandoned their attempt even after being promised $1.3 billion in funding from the European Union. Luminaries like Mila founder Yoshua Bengio and Facebook VP and chief AI scientist Yann LeCun have repeatedly argued that AGI isn’t technically feasible.

Questions of practicality aside, to Socher’s point, AGI might be overkill for some of what Sanctuary hopes to achieve. Aeolus — a large, humanoid janitorial robot that’s heavy enough to do serious damage to any person in its path — takes a full minute to pick up a stuffed animal and put it in a nearby bin. On the other hand, Berkeley, California-based Covariant — which has backing from Yann LeCun, among others — claims to have developed a special-purpose system capable of picking and packing some 10,000 different kinds of objects with 99% accuracy.

Beyond fulfillment, robots exist that can tackle many of the challenges that Sanctuary lists in its press release. Robots have been used to dispose of landmines for over a decade, and during the pandemic, machines came into wide use for sterilizing not just hospitals but offices and public spaces. Robots for space exploration are nothing new either — the first rover in space — the Soviet Union’s Lunokhod 1 — made a successful moon landing in 1970. NASA flew several humanoid robots in space in the early 2000s.

To be sure, the robots of today are far from perfect. Grasping objects remains a difficult challenge. Prototype household robots like PR2, developed by researchers at the University of Bremen, can’t reliably hold objects like spoons and milk cartons. Tightening or loosening bolts, tearing up a paper towel, pouring water, opening a bottle with a locking safety cap, and other tasks humans complete easily require precise motions with which many machines struggle. But existing techniques — including RL — will likely be sufficient to solve many of these problems, according to Mike Cook, a member of the Knives & Paintbrushes AI research collective.

“I’ve never seen any convincing reason for why AGI would be more useful than specialized systems, except in situations so hypothetical they might as well be paperback novels in airport shops,” Cook told VentureBeat via email. “This is buck wild.”

VentureBeat’s mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More

You must be logged in to post a comment.