Reynold Ruffins, an illustrator, graphic designer and artist who was an early member of Push Pin Studios, the impish and buzzy design firm founded by his Cooper Union classmates Milton Glaser, Ed Sorel and Seymour Chwast, died July 11 at his home in Sag Harbor, New York. He was 90.

The cause was cardiac arrest, his son Seth Ruffins said.

Print advertising in the early 1950s was a formal, rather dull affair. Products were mostly hawked using traditional typefaces paired with romantic or idealized photographs and illustrations on the one hand, or a chilly, rational European modernist style — elegant photographs and sans serif type — on the other.

In witty, faux-nostalgic drawings and lettering, Glaser, Chwast, Sorel and Ruffins, all illustrators, turned the field on its head, and in so doing largely created the postmodern discipline of graphic design, by taking what had been disparate roles — illustration and type design — and putting them together.

“They made entertainment out of design,” said Steven Heller, a former art director at The New York Times Book Review and editor of “The Push Pin Graphic: A Quarter Century of Innovative Design and Illustration,” a 2004 visual history of the studio’s work. “They did it by using vernacular forms like cartoon, and by going back into styles like art nouveau and art deco and reinterpreting them. They brought passe back. They brought pastiche into the vocabulary of design and made it cool.”

In his own work, Ruffins mined late-19th century and early-20th century European imagery such as the posters and illustrations of Emil Pretorius or Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch, a German cartoonist and illustrator. The kinetic looniness of the German cartoons and the billowing forms of art nouveau taken up by Ruffins and the other Push Pin illustrators prefigured the trippy, psychedelic imagery that would become the signature look of the late ’60s.

“Reynold played with the forms,” Heller said. “While they fit into the 20th-century continuum, they are definitely his own.”

As Ruffins recalled later, being Black made him a rarity in the advertising business — an industry that, before the civil rights era, was an all-white world of people similar to characters in the TV series “Mad Men.” Since his work was his calling card, clients often did not know his race.

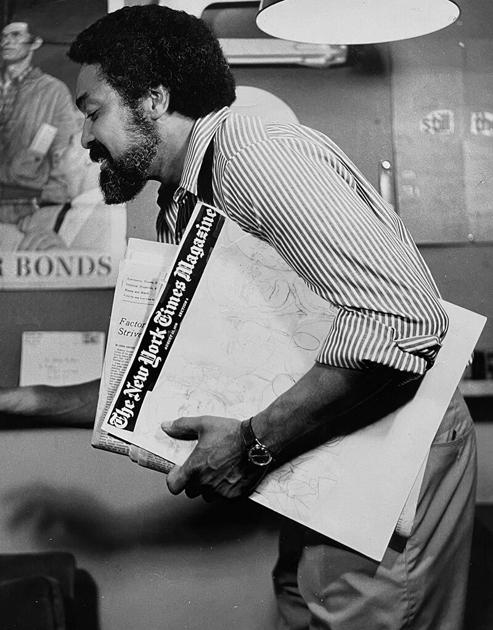

“After finishing a job, I’d go meet an art director and there would be some surprises,” Ruffins told the Sag Harbor Express in 2013. “One time, I finished a big job — both physically and financially — and had my portfolio under my arm. I was feeling so good. The receptionist looked up and said, ‘The mailroom’s that way.’ The assumption was if you were Black, you were delivering something.”

Reynold Dash Ruffins was born Aug. 5, 1930, in the New York City borough of Queens. His father, John Ruffins, was an appliance salesperson for Consolidated Edison, otherwise known as Con Ed, the energy company; his mother, Juanita (Dash) Ruffins, was a homemaker.

Like Glaser, a high school buddy, Reynold Ruffins went to the High School of Music & Art and then Cooper Union, the highly selective and, at the time, tuition-free arts college in downtown Manhattan. Ruffins graduated in 1951.

One summer, he and his classmates there, Glaser and Chwast, formed a graphics business called Design Plus. They had two clients, Chwast recalled. One wanted to make a gross of cork place mats (Ruffins designed the tropical scene that they silk-screened onto them), and the other was a monologuist who needed a flyer. “Then our vacation was over, and we went back to school,” Chwast said.