Becoming a machine learning engineer still isn’t quite as straightforward as becoming a web or mobile engineer, as we discussed in Part 1 of this series. This is despite all of the new programs geared toward machine learning both inside and outside of traditional schools. If you ask many people with the title of “Machine Learning Engineer” what they do, you’ll often get wildly different answers.

The goal of this post is to help you put together the beginnings of a mental semantic tree (Khan Academy’s example of such a tree) for learning machine learning (à la Elon Musk’s now famous method). As such, this post is probably going to have a bit more lists and hyperlinks than previous (or future) posts in this series.

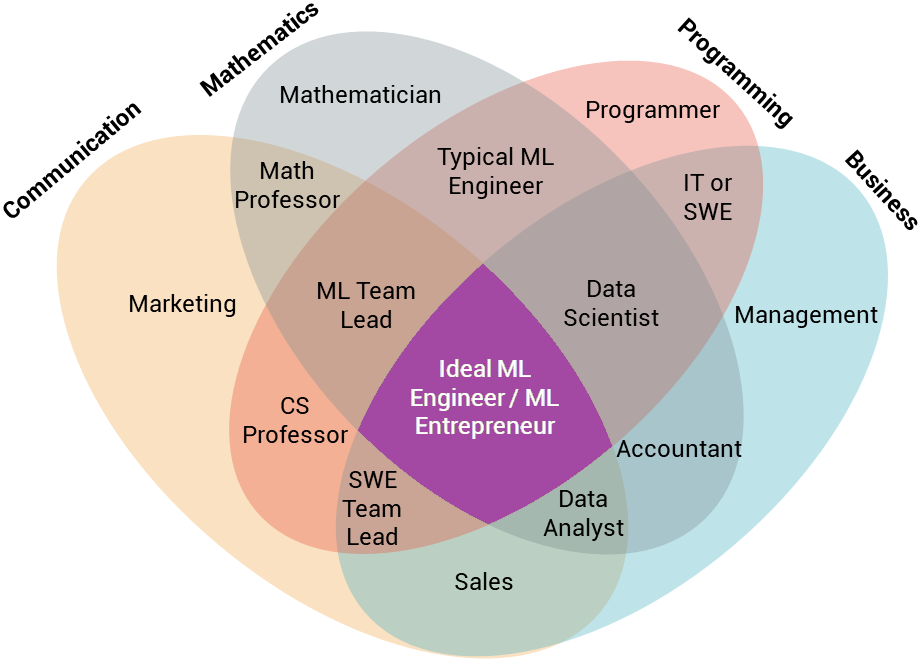

So, based on my own experiences, as well as reaching out to hundreds of machine learning engineers in both academia and industry, here’s an overview of the soft skills, basic technical skills, and more specialized skills you’ll need.

Before we go into the technical qualifications, we need to cover a few non-technical skills that you should keep in mind before diving into the deep end. Yes, machine learning is mainly math and computer science knowledge. However, you’ll most likely need to find ways of applying this to solve real problems.

Learning new skills: The field is rapidly changing. Every month new neural network models come out that outperform previous architecture. GPU-manufacturers are in an arms race. 2017 saw just about every major tech giant release their own machine learning frameworks. There’s a lot to keep up with, but luckily the ability to quickly learn things is something you can improve on (Growth mindsets for the win!). Classes like Coursera’s Learning how to Learn are great for this. If you have Dyslexia, ADD, or anything similar, the Speechify app can offer a bit of a productivity boost.

Muad’Dib learned rapidly because his first training was in how to learn. And the first lesson of all was the basic trust that he could learn. It’s shocking to find how many people do not believe they can learn, and how many more believe learning to be difficult. Muad’Dib knew that every experience carries its lesson.

– Dune, by Frank Herbert

Time-management: A lot of my friends have gone to Ivy League schools like Brown, Harvard, and MIT. Out of the ones that made it there and continued to succeed afterwards, it seemed that skill in time management was a much bigger factor in their success than any natural talent or innate intellect. The same pattern will likely apply to you. You’ll often find that for many projects, the time to train models is a major bottleneck, especially when you’re pushing the limits of your hardware. When it comes to a cognitively-demanding task like machine learning, I cannot recommend highly enough Cal Newport’s book “Deep Work” (or his Study Hacks Blog). If you’re still in college or high school, Jessica Pointing’s Optimize Guide is also a great resource. I’ll go into more resources like this in the next post in this series.

Business/Domain knowledge: The most successful machine learning projects out there are going to be those that address real pain points. It will be up to you to make sure your project isn’t the machine learning equivalent of Juicero. In academia, the emphasis is more on the side of improving metrics of algorithms. In industry, the focus is all about making those improvements count towards solving a real-world problem. Beyond taking classes in entrepreneurship while you’re in school, there are plenty of classes online that can also help (Coursera has a pretty decent selection). One of the more useful online resources out there I’ve seen is the Smartly MBA. It’s creators impose a low acceptance rate, but if you get in it’s free. At the very least, business or domain knowledge helps a lot with feature engineering (many of the top-ranking Kaggle teams often have at least one member whose role it is to focus on feature engineering).

Communication: You’ll need to get past interviews. You’ll need to explain ML concepts to people with little to no expertise in the field. Chances are you’ll need to work with a team of engineers, as well as many other teams. Communication is going to make all of this much easier. If you’re still in school, I recommend taking at least one course in rhetoric, acting, or speech. If you’re out of school, I can personally attest to the usefulness of Toastmasters International.

Rapid Prototyping: Iterating on ideas as quickly as possible is mandatory for finding one that works. In machine learning, this applies to everything from picking the right model, to working on projects such as A/B testing. I had the pleasure of learning a lot about rapid prototyping from one of Tom Chi’s prototyping workshops (he’s the former Head of Experience at GoogleX, and he now has an online class version of his workshop). Udacity also has a great free class on rapid prototyping that I highly recommend.

Okay, now that we’ve got the soft skills out of the way, let’s get to the technical checklist you were most likely looking for when you first clicked on this article.

Python (at least intermediate level) — Python is the lingua franca of Machine Learning. You may have had exposure to Python even if you weren’t previously in a programming or CS-related field (it’s commonly used across the STEM fields and is easy to self-teach). However, it’s important to have a solid understanding of classes and data structures (this will be the main focus of most coding interviews). MITx’s Introduction to Computer Science is a great place to start, or fill in any gaps. In addition to intermediate Python, I also recommend familiarizing yourself with libaries like Scikit-learn, Tensorflow (or Keras if you’re a beginner), and PyTorch, as well as how to use Jupyter notebooks.

C++ (at least intermediate level) — Sometimes Python won’t be enough. Often you’ll encounter projects that need to leverage hardware for speed improvements. Make sure you’re familiar with basic algorithms, as well as classes, memory management, and linking. If you also choose to do any machine learning involving Unity, knowing C++ will make learning C# much easier. At the very least, having decent knowledge of a statically-typed language like C++ will really help with interviews. Even if you’re mostly using Python, understanding C++ will make using performance-boosting Python libraries like Numba a lot easier. Learn C++ has been one of my favorite resources. I would also recommend Programming: Principles and Practice Using C++ by Bjarne Stroustrup.

Once you have the basics of either Python or C++ down, I would recommend checking out Leetcode or HackerRank for algorithm practice. Quickly solving basic algorithms is kind of like lifting weights. If you do a lot of manual labor (e.g., programming by day), you might not necessarily be lifting a lot of weights. But, if you can lift weights well, most people won’t doubt that you can do manual labor.

Onward to the math…

Linear Algebra (at least basic level) — You’ll need to be intimately familiar with matrices, vectors, and matrix multiplication. Khan Academy has some good exercises for linear algebra. I also recommend 3blue1brown’s YouTube series Essence of Linear Algebra for getting a better intuition for linear algebra. As for textbooks, I would recommend Linear Algebra and Its Applications by Strang & Gilbert (for getting started), Applied Linear Algebra by B. Noble & J.W. Daniel (for applied linear algebra), and Linear Algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics by Werner H. Greub (for more advanced theoretical aspects).

Calculus (at least basic level) — If you have an understanding of derivatives and integrals, you should be in the clear. Otherwise even simpler concepts like gradient descent will elude you. If you need more practice, Khan Academy is likely the best source of online practice problems out there for differential, integral, and multivariable calculus. Differential equations are also helpful for machine learning.

Statistics (at least basic level) — Statistics is going to come up a lot. At least make sure you’re familiar with Gaussian distributions, means, and standard deviations. Every bit of statistical understanding beyond this helps. Some good resources on statistics can be found at, you probably guessed it, Khan Academy. Elements of Statistical Learning, by Hastie, Tibshirani, & Friedman, is also great if you’re looking for applications of statistics to machine learning.

BONUS: Physics (at least basic level) — You might be in a situation where you’d like to apply machine learning techniques to systems that will interact with the real world. Having some knowledge of physics will take you far. For learning physics online, I would point to Physics for the 21st Century, MIT’s online physics courses, UC Berkeley’s Physics for Future Presidents, and Khan Academy. For textbooks, I would look at Frank Firk’s Essential Physics 1.

BONUS: Numerical Analysis (at least basic level) — A lot of machine learning techniques out there are just fancy types of function approximation. These often get developed by theoretical mathematicians, and then get applied by people who don’t understand the theory at all. The result is that many developers might have a hard time finding the best technique for their problem. If they do find a technique, they might have trouble fine-tuning it to get the best results. Even a basic understanding of numerical analysis will give you a huge edge. I would seriously look into Deturk’s Lectures on Numerical Analysis from UPenn, which covers the important topics and also provides code examples.

All this math might seem intimidating at first if you’ve been away from it for a while. Yes, machine learning is much more math-intensive than something like front-end development. Just like with any skill, getting better at Math is a matter of focused practice. There are plenty of tools you can use to get a more intuitive understanding of these concepts even if you’re out of school. In addition to Khan Academy, Brilliant.org is a great place to go for practicing concepts such as linear algebra, differential equations, and discrete mathematics.

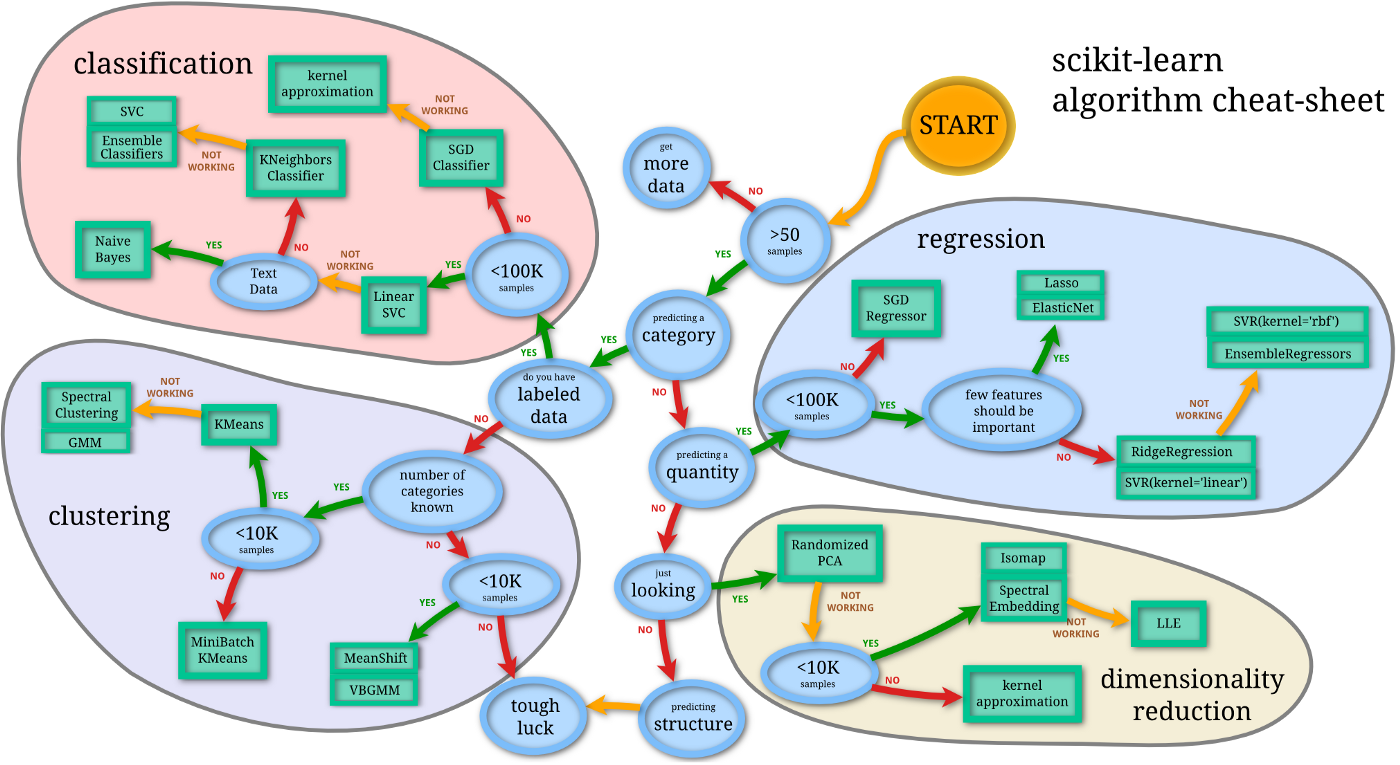

Common non-neural network Machine Learning Concepts — You may have decided to go into machine learning because you saw a really cool neural network demonstration, or wanted to build an artificial general intelligence (AGI) someday. It’s important to know that there’s a lot more to machine learning than neural networks. Many algorithms like random forests, support vector machines (SVMs), and Naive Bayes Classifiers can yield better performance for your hardware on some taks. For example, if you have an application where the priority is fast classification of new test data, and you don’t have a lot of training data at the start, an SVM might be the best approach for this. Even if you are using a neural network for your main training, you might use a clustering or dimensionality-reduction technique first to improve the accuracy. Definitely check out Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning, as well as the Scikit-learn documentation.

Common Neural Network Architectures – Of course, there are still good reasons for the surge in popularity of neural networks. Neural networks have been by far the most accurate way of approaching many problems, like translation, speech recognition, and image classification. Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning (and his more up-to-date Deep Learning specialization) are great starting points. Udacity’s Deep Learning is also a great resource that’s more focused on Python implementations.

Bear in mind, these are mainly the skills you would need to meet the minimum requirements for any machine learning job. However, chances are you’ll be working on a very specific problem within Machine Learning. If you really want to add value, it will help to specialize in some way beyond the minimum qualifications.

Computer Vision — Out of all the disciplines out there, there are by far the most resources available for learning computer vision. Getting a convolutional neural network to get high accuracy on MNIST is the “hello world” of machine learning. This field appears to have the lowest barriers to entry, but of course this likely means you’ll face slightly more competition. A variant of Georgia Tech’s Introduction to Computer vision is available for free on Udacity. This is great if you supplement this course with O’Rieley’s Learning OpenCV and Richard Szeliski’s Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications (he’s the founding director of the Computational Photography group at Facebook). I also recommend checking out the Kaggle kernels for Digit recognition, Dogs vs Cats classification, and Iceberg recognition.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) — Since it combines computer science and linguistics, there are a bunch of libraries (Gensim, NLTK) and techniques (word2vec, sentiment analysis, summarization) that are unique to NLP. The materials for Stanford’s CS224n: Natural Language Processing with Deep Learning class are readily available to non-Stanford students. I also recommend checking out the Kaggle kernels for the Quora Question Pairs challenge and Toxic Comment Classification Challenge.

Voice and Audio Processing — This field has frequent overlap with natural language processing. However, natural language processing can be applied to non-audio data like text. Voice and Audio analysis involves extracting useful information from the audio signals themselves. Being well versed in math will get you far in this one (you should at least be be familiar with concepts like fast Fourier transforms). Knowledge of music theory also helps. I recommend checking out the Kaggle kernels for the MLSP 2013 Bird Classification Challenge and TensorFlow Speech Recognition Challenge, as well as Google’s NSynth project.

Reinforcement Learning — Reinforcement learning has been a driver behind many of the most exciting developments in deep learning and artificial intelligence in 2017, from AlphaGo Zero to OpenAI’s Dota 2 bot to Boston Dynamics’s Backflipping Atlas. This is will be critical to understand if you want to go into robotics, Self-driving cars, or any other AI-related area. Georgia Tech has a great primer course on this available on Udacity. However, there are so many different applications, that I’ll need to write a more in-depth article later in this series.

There are definitely more subdisciplines to ML than this. Some are larger and some have yet to reach maturity. Generative Adversarial Networks are one of these. While, there is definitely a lot of promise for their use in creative fields and drug discovery, they haven’t quite reached the same level of industry maturity as these other areas.

BONUS: Automatic Machine Learning (Auto-ML) — Tuning networks with many different parameters can be a laborious process (in fact, the phrase “graduate student descent” refers to getting hordes of graduate students to tune a model over the course of months). Companies like Nutonian (bought by DataRobot) and H2O.ai have recognized a massive need for this. At the very least, knowing how to use techniques like grid search (like scikit-learn’s GridSearchCV)and random search will be helpful no matter your subdicipline. Bonus points if you can implement techniques like bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms.

With this overview of machine learning skills, you should hopefully have a better grasp on how the different parts of the field relate to one another. If you want to get a quick, high-level understanding of any of these technical skills, Siraj Raval’s YouTube channel and KDnuggets are good places to start.

The next post will focus on improving your productivity while improving your skills. We covered productivity a little bit in this post, but it’s probably worth going into more depth.

You can read Part 1 of this series here.