ST. GEORGE — Shortly before the outbreak of World War II a new movement in architecture, art, sculpture and design began to take shape.

Although it’s hard to pin down what form of artistic expression came first – modern furniture, art or architecture – many believe it is found in furniture and the ground-breaking use of polished steel tubes, leather, molded plastic, fiberglass and the application of shaped plywood that can still be found in many retail stores today.

Nearly a decade after the birth of what would become the “modern movement,” the next generation of artisans – such as Harry Bertoia – soon expanded the design to combine clean lines in furniture and a minimal, functional, symmetrical and utilitarian conceptualization of use that still appeals to consumers today.

Born in Italy on March 10, 1915, Harry Bertoia showed great aptitude and love for art as a child.

“He always knew that he wanted to be involved with art,” said his daughter, St. George resident Celia Bertoia. “When he was a teenager in rural Italy, anytime he had a spare moment he would draw.”

To keep the memory and legacy of her late father alive, Celia Bertoia started the Harry Bertoia Foundation in 2013, which commemorates his birth, his work and his life.

To celebrate the foundation is hosting a “Birthday Bash,” scheduled from noon to 4 p.m., March 10 at the St. George art studio. Sonambient concerts are planned and refreshments will be served.

“We open up our doors to honor a lifelong love affair of his work,” Bertoia said. “Every day I get a feeling that Harry is smiling down at me and pleased that we keep his memory alive.”

The beginnings of modern/mid-century design

In the early 1900s, a new style of furniture emerged.

Modern furniture was designed to be light in form and color, combining clean geometric lines with materials that reflected the industrial age and its processes.

One of the progenitors of the new movement was Le Corbusier, a Swiss-born architect and designer.

It was reported that Le Corbusier described the birth of modernism as the start of a “great epoch” where a “new spirit” of design had begun.

Modern furniture design was predominantly influenced by the German Werkbund and Bauhaus schools of design.

In 1925, Marcel Breuer, a member of the Bauhaus school, designed one of the most iconic pieces of modern furniture called the Wassily Chair – after Wassily Kandinsky, an influential artist of his day.

In little more than a decade, the next generation of modern artists – including Harry Bertoia – expanded the concept of this avant-garde style of expression that is still found in paintings, sculptures, architecture and furniture today.

Bertoia – The molding of an artist

At the age of 15, Bertoia’s parents noticed he had an innate talent to create. His parents gave their son a choice, either attend art school in Venice or immigrate to America where his older brother – Oreste – lived in Detroit.

Taking a leap of faith, Bertoia’s choice was clear, his daughter Celia said, it was America and the opportunity for adventure and new beginnings.

“He had never traveled before,” Bertoia said. “He would go as far as he could on his bicycle, and when he immigrated to the Detroit area it was really a culture shock.”

Arriving in America in 1930, Bertoia learned English and advanced math, the bus schedule and the joys of eating hamburgers, a culinary delight not found in Europe.

Bertoia attended Cleveland Elementary School to catch up in basics – only going as far as the fifth grade in Italy – before enrolling in Cass Technical High School, where he studied art and design and learned the skill of crafting jewelry.

In 1936, Harry attended the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts, now known as the College for Creative Studies.

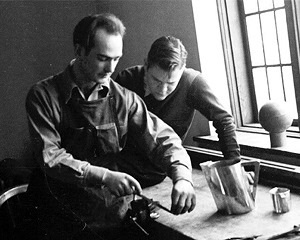

The following year, Harry received a scholarship to study at the Cranbrook Academy of Art where his tutelage began under artistic stalwarts such as Walter Gropius, Edmund Bacon, Ray and Charles Eames, and Hans and Florence Knoll.

Along with influence from architects and furniture designers, Bertoia developed a love for working with metal. Because of his vision and craftsmanship, Bertoia would eventually work for both Eames and the Knoll Company.

“I think the reason ‘modern’ furniture has stood the test of time is because of its timelessness,” Celia Bertoia said. “This type of furniture can go into any kind of house from an old farmhouse to a modernist, contemporary, designed home.”

Bertoia – The coming of age

In 1950, Harry was invited to Pennsylvania to work with Knoll.

During this period Harry Bertoia designed wire furniture that became known as the Bertoia Collection for the Knoll company. Among these was the famous ‘diamond chair,’ a fluid, sculptural form made from a welded latticework of steel.

In Harry Bertoia’s original presentation of his wire chairs to Hans and Florence Knoll in 1950, he also showcased a chaise lounge version, essentially the large diamond chair extended on two of its sides. Because of its design, the term asymmetric became a reference to its shape.

At that time, the complexity of production with some of Bertoia’s furniture was still years from being resolved by Knoll Design and Development, and as a result, the decision was taken to not develop the chaise.

However, the asymmetric chaise lounge was brought to life after more than five decades of conceptual ideas sitting on a shelf.

In 2003, two prototypes were made.

One chaise was sold at auction for $119,000. At that point, Knoll obtained access to the chaise and used its specifications as a model for reproduction.

Although Knoll would eventfully crack the manufacture conundrum through computer-aided design and 20th-century manufacturing techniques – to this day – Bertoia’s furniture requires the intricacies of hand welding.

The chair and chaise lounge have gone on to enjoy worldwide acclaim and are still produced today.

It was a very special time in Harry Bertoia’s life, his daughter said.

“Happily, after World War II there was a group of inspired designers to fulfill the needs of a (growing) middle class,” Celia said. “When Harry met all of these creative spirits … Eero Saarinen, Paul Clay, Kandinsky and other designers, artists and architects with really different ideas … they began to percolate in Harry Bertoia’s head.”

Celia added that her father took the kernel of each design style and experimented with its form and function.

“Harry would say, ‘the comfort of the person using the furniture was most important,’” she added. “But, it was also about the appearance.”

Working in metal and wire was Bertoia’s sweet spot.

When Knoll realized they had a “winning” designer in-house, the company worked to resolve the obstacles for mass production – a definite requirement to make a profit.

“It was very challenging for Knoll because they had been using wood and all the machinery was geared toward using this material for furniture,” Celia said. “Trying to pivot to using metal they could not do it at first. They had to come up with new equipment.”

Bertoia – And the Rest is History

Harry Bertoia would become a world-renowned mid-century furniture designer whose furniture is still in production. Only a few other furniture lines have had the linage and wherewithal to enjoy this gravitas.

Critical acclaim brought artistic success.

In the mid-1950s, the Bertoia’s chairs sold so well that Knoll paid the artist a lump sum that allowed Bertoia to devote himself exclusively to sculpture.

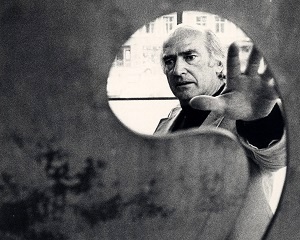

From 1953 to 1978, Harry Bertoia was commissioned to craft numerous large sculptures.

During his life, Harry Bertoia made more than 50 public sculptures, which are still on display in cities throughout the United States as well as abroad. Bertoia was also commissioned to produce pieces for arguably some of the greatest architects of their time including Henry Dreyfuss, Roche & Dinkeloo, Minoru Yamasaki, Edward Durell Stone and I M Pei.

Bertoia – Sound Sculpture

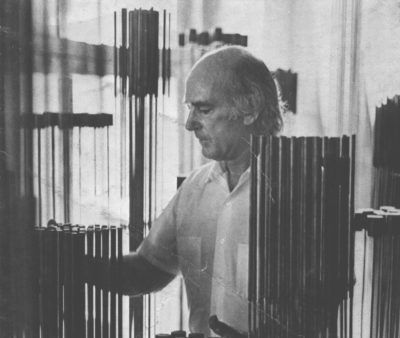

In the 1960s, Bertoia joined a few artists to create “sonambient” sound sculptures, a musical instrument using rods and wires that acoustically resonate when struck against each other.

With a renewed sense of artistic inspiration, Bertoia renovated an old barn into a concert hall that combined about 100 of his favorite “sonambient” sculptures where he would play the pieces in a series of concerts.

Bertoia would also produce 11 albums, entitled “Sonambient.”

The music, his contemporaries said, was a true and honest form of his art that was manipulated by hand along with taking advantage of elements found in nature.

“Harry really didn’t see any boundaries or labels,” Celia Bertoia said. “People were always trying to label his work or give them special names, but he really didn’t like to title his work. He said, ‘it’s really up to the viewer to decide what they think it is.’ Everyone has their own interpretation, of what Harry did, and that is kind of the fun of his work.”

Bertoia’s sounding sculptures can be found at the St George gallery, in the plaza of the Aon Center – Chicago’s third-tallest building – and in the Rose Terrace at Chicago’s Botanic Garden.

Bertoia – His Death

Bertoia died on Nov. 6, 1978, of lung cancer in Barto, Pennsylvania, at the age of 63.

It was believed that some of the materials he used were dangerous.

“He used copper-beryllium in his welding and when heated it emits toxic fumes,” Celia Bertoia said. “Even though the suppliers warned him to use a mask he didn’t want to protect himself. He said ‘a mask would prevent him connecting with his work.’”

When Bertoia was first diagnosed he had about one year left to live.

Described as a “strong and vibrant” person, Harry Bertoia resisted the disease with all of his might.

“He worked until he literately could not do it anymore,” Celia said. “He withered away and succumbed to the disease, but he had a very full and productive life and said he was pretty satisfied with what he was able to accomplish.”

The Harry Bertoia Foundation is located at 1449 N. 1400 West, Suite 11, St. George. For more information, call 435-673-2355.

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2022, all rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.