A personal view from Ian Stewart, Deloitte’s Chief Economist in the UK.

In late 2019, Deloitte wrote a Briefing arguing that the car industry is a bellwether of the global economy and of globalisation. A few months later the sector faced the most destructive downturn since the financial crisis.

Lockdowns led to a collapse in car travel, shuttered car dealers and disrupted factory operations. Global car production plunged. In the UK output dropped by 29 per cent last year to the lowest level since 1984. The experience of the global financial crisis, from which European car sales have never recovered, pointed to a lasting long-term hit to demand.

Carmakers and parts suppliers responded by scaling back production, cutting orders for components and running down inventories.

But much like the global economy itself, demand for cars has snapped back faster than expected. Governments have propped up consumer incomes while lockdowns have led to an enforced rise in savings. Cheap money has pushed up the price of houses and equities, buoying household wealth.

Consumer balance sheets – and spending power – are stronger than they were a year ago. Add in cheap financing costs, and the appeal of personal – as opposed to public – transport, and the stage was set for a rebound in car sales and use.

According to TomTom traffic data, congestion levels are now above pre-pandemic levels in major UK cities. Bloomberg reports that in Shizuoka Prefecture in Japan, applications for driving licences have risen sharply among people in their 20s, reversing a pre-pandemic trend of declining car ownership among young people.

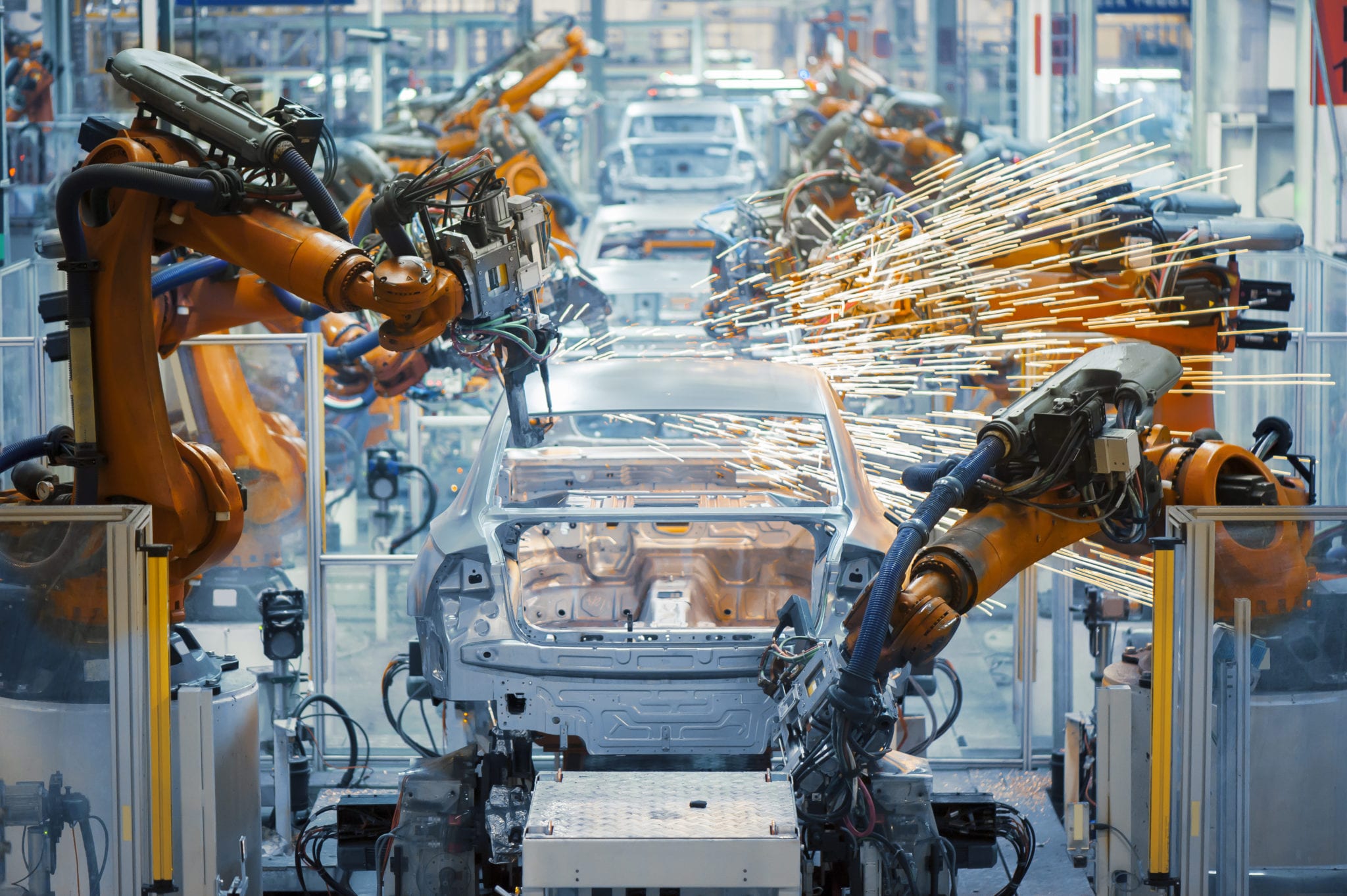

Many automakers started 2021 with record sales. Now they are struggling to meet demand, partly as a result of a global shortage of semiconductors. Cars increasingly use chips, for everything from engine and transmission control to safety and entertainment. The auto sector accounted for about 10 per cent of global chip demand in 2019.

The global chip crunch in turn reflects shifting consumer demand, supply chain frictions, geopolitical tensions and extreme weather.

During the pandemic consumer demand surged for many manufactured goods, ranging from smartphones to household appliances, which use the same basic chips as cars. Chip suppliers struggled to meet the demand due to inadequate production capacity, having invested in more advanced chips for areas like 5G prior to the pandemic. Extreme weather in Texas, a fire at a Japanese chip factory, a drought in Taiwan (chipmaking is water-intensive) and Chinese stockpiling of chips to forestall possible US export controls added to the chip crunch. The Wall Street Journal reported on Friday that the shortage is spilling into other industries, hitting “makers of home appliances, heavy equipment, servers and sex toys”.

Many automakers have had to slash production forecasts, cut hours and even idle factories. IHS Markit estimates that the chip shortage reduced global car production by 700,000 between January and March. Chipmakers warn that shortages could persist into next year.

The pandemic has caused huge disruptions, but for the car industry the transition to electric vehicles (EVs) represents a far more profound shift. In this area, as in many others, the pandemic has accelerated the pace of change.

Global vehicle sales fell by 16 per cent in 2020 while EV sales jumped by 40 per cent alongside a surge in EV-related equities, most notably Tesla (a $1 invested in Tesla a year ago is worth $4.22 today). This is in contrast to the global financial crisis, when ‘green’ stocks plunged and failed to recover over the following decade. More demanding climate change targets are feeding directly, and as intended, into EV sales. The numbers, admittedly from a low base, are arresting.

Last November the UK government announced a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2030. In the first three months of this year petrol car sales fell by 28 per cent compared with a year earlier while EV sales rose by 74 per cent. This year the UK’s Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders estimates that EVs will take a record 14 per cent of the UK car market, up from virtually nothing ten years ago. In the euro area tighter emissions standards spurred a 137 per cent surge in EV sales last year.

Automakers have announced ambitious EV production targets and are competing to secure the most advanced battery technology. The importance of semiconductors will increase, with EVs even more chip-intensive than petrol cars.

Faced with rising geopolitical tensions, particularly with China, and growing demand for EVs, Western governments are seeking to expand domestic battery production capacity and ensure access to the raw materials. Unlike chips, batteries are heavy, which means EV production is best located near battery plants. Global battery production, like semiconductor manufacturing, is dominated by East Asian countries, and global car production has long been shifting towards Asia.

In December a start-up, Britishvolt, announced the construction of the UK’s first battery gigafactory in Blyth – welcome news for the future of UK EV production. Europe and the US have ambitious plans to invest in domestic battery production. The effort is starting to bear fruit, with euro area battery production rising by almost a third in February on a year earlier.

Automakers are retooling their production for EVs and pouring capital into battery technology. Like all previous energy transitions, the shift to EVs will require huge levels of investment.

The auto industry is a microcosm of the forces that will shape this decade: technological change, climate, the rise of Asia, reshoring and geopolitics. Batteries and semiconductors have become increasingly strategic sectors. Their supply depends on a global trading system that faces greater strains. The auto sector is at the front end of a historic economic and geopolitical change.