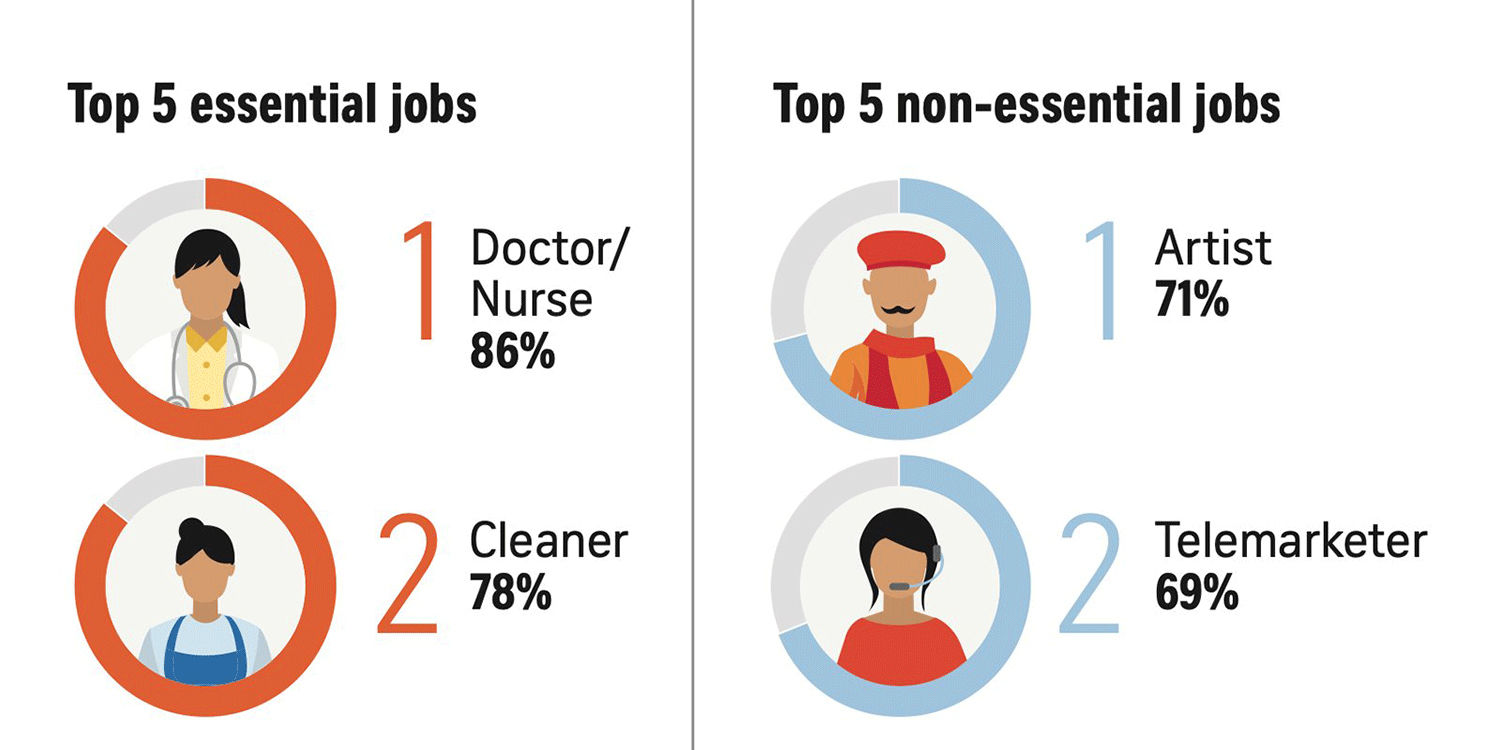

A look at how essential your job is to society.

A poll published yesterday in Singapore by The Sunday Times shows 71% of locals think artist is the most ‘non-essential’ job during a pandemic. As you can guess, such results provoked debate among artists and illustrators both and in and out of Singapore, and has raised discussion on just how artists have survived the ongoing Corona-era – and how well they might survive the crisis should it die down.

Speaking with illustrators, designers and agency heads, Digital Arts today investigates the impact of the 2020 crisis upon artists, exploring the UK Government’s attitude towards freelancers – which most creatives categorise themselves as – and how it translates to its general attitude towards the UK creative industry as a whole. In other words, does society treat its artists as essential or not?

How little Boris cares about you

“I’ve always felt that UK culture understands and values the creative industry but whether the Government does or not, I can’t really comment,” says Sheffield illustrator Geo Law when I ask whether the UK Government under PM Boris Johnson understands and supports creativity in general.

“They like to promote and raise awareness of the tech industry as it’s flashy and shiny but fail to realise every industry or product requires visual communicative processes such as graphic design, illustration, photography and videography to help support and sell these things. I feel it’s always been a case of ‘it’s a background thing’ which only industry peers really take note of.”

Geo raises a good point, especially in the light of how visual communication was fundamental to the UK lockdown’s messaging: who among us didn’t see and understand the yellow and green graphics asking us to ‘stay home and save lives’? Arguably that message was understood by many in the country, but it remains to be seen whether that’ll register as a newfound appreciation for the importance of visual creatives.

“The public probably know more about fine art than they do illustrators and graphic designers thanks to public museums, the Turner Prize and so forth,” Geo continues. “I feel the Government and the public in general see that side of the creative arts for what it is: as a service, and not as a highly regarded art form of communication.”

Colin ‘Alt Aesthetics’ Kersley adds that “there has been an entrenched stigma associated with creativity in the UK for so long that it isn’t considered a ‘real’ career by so many people.”

“Funding and educational cuts always hit the creative sector,” he writes, “which means that it heavily relies on individuals turning their passions into businesses with very little support. Despite all of that, the creative industries contribute more to the economy than the oil, gas, automotive, sciences, and aerospace industries combined, which is pretty incredible.”

Lisa Maltby meanwhile reminds me that while the creative industry contributes £10.8 billion to the UK economy, government arts funding has fallen 35% over the last decade. But it isn’t just an issue about money, as demonstrated by the Corona-crisis.

“Without creativity, vital information would be less accessible and businesses less engaging, meaning other industries would also suffer,” Lisa says. “Creativity has also been essential for the country’s wellbeing during the pandemic, keeping us entertained, focussed and connected.

“We take for granted what the world would be like without film, music or art and how that would impact our mental health and wellbeing.”

S.O.S. S.E.I.S.S

The ‘acid test’ of whether the Government cares about the arts can be seen in its aid towards freelancers at the start of the Corona-panic. While this may not be of interest to those who believe being an artist is a non-essential career, the attitude towards the self-employed at large should set alarm bells ringing for many.

Illustrator Katie Chappell tells me that “from a purely selfish standpoint”, the money from the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) has been gratefully received.

“80% of my live illustration work was cancelled in the week before the UK lockdown,” as she explains. “Knowing that, because of the SEISS I’d be able to pay my rent — even if no more work came in at all — was a relief.”

But like many, the artist still has her concerns about the scheme, the sort shared by book designer and paper engineer Helen Friel.

“The time that the Government has taken to put self-employed help in place has shown they have very little understanding of people who work for themselves,” says Helen. “The two months it’s taken to receive help will have been too long for many small businesses.

“This Government has put a lot of energy into persuading people to become self-employed but when we’ve needed their support it’s felt very much like an afterthought. The fact that there has been uncertainly around whether self-employed people will receive the same help as furloughed workers is unforgivable.

“I’m extremely grateful that the help has finally come through for many of us, but there are still self-employed people, like directors of limited companies, that are falling through the cracks.”

Image: Getty

Image: GettyChildren’s book illustrator Emma Reynolds concurs about such cracks, having fallen through them herself.

“I’ve been self employed for nearly 10 years, but because I also had a PAYE job that ended two years ago, I wasn’t eligible because I was over the 50% mark by a small amount,” Emma tells me. “Many freelance gigs are forced to be put on PAYE contracts, so this is very unfair, and shows the Government’s lack of understanding or care about the self-employed gig industry.”

“I think it shows that there is a huge disparity between how the Government deals with the self employed VS salaried ‘PAYE people,'” adds Roar agency head Skye Kelly-Barrett. “It really felt like the support given during the crisis was very minimal and didn’t really take all things into consideration when working out if and how people would be given financial help, whilst those on PAYE schemes have the opportunity to be furloughed, with salary covered up to a percentage each month regardless.

“I believe a lot of the campaigning helped push the government to really look at what they were doing for the freelance community and try to do more, and who knows if that would have happened if people hadn’t fought so hard to have their voices heard. But, it still feels like many people have been left behind and not approved for the kinds of help they deserve; as we all pay our taxes, we should all qualify for help.”

Image: Getty

London illustrator Sneha Shanker was one of those who didn’t qualify for help, due to not having tax returns for the last three years.

“The Dutch government has provided much better relief to the freelancers whose income has been hit by giving a subsidy of up to €1,050 per month for single people (without any prerequisite conditions or checks),” Sneha says as comparison. “We are not seeing such grants available here (so) I think the government could have done much better in terms of support for the freelance community considering a whole lot of the population is freelancing now.”

Artist Hazel Mead tells me that when the SEISS scheme was finally amended to cater for the self-employed like her, she realised it “wouldn’t be helpful at all.”

“They would base it on previous tax returns which seems fair, but on my 2018 tax return I didn’t make any profit from the business,” she reveals. “I had jobs supporting me whilst I built my freelance client base. Based on that tax return I wouldn’t receive any support, even though the following year and this year I’m clearly earning a lot more through my full time business. I considered looking deeper but I thought it best to focus my energy on clients.”

‘Creativity is dangerous’

Moving away from economics, Hazel believes how essential the arts are seen by the UK and its leaders can be found in how it is taught in schools.

“I have never thought of the government as encouraging of creativity. I think that view has been instilled in me from a young age. My headteacher wasn’t supportive of it and actually said ‘Creativity is dangerous’,” she remembers. “Even throughout university, the lecturers instilled this sense of needing to be self-sufficient as an artist; I don’t remember there being any mention of government help schemes specifically for artists. There’s the Arts Council of course, but that always felt more for fine artists than illustrators.

Bristolian artist Dave Bain hopes this attitude can one day be turned around with “access to art education for all people, regardless of their background.”

“I believe the arts have an enormous impact on the wellbeing and health of different communities across the whole country,” he says. “Ensuring all voices are heard is vital to bringing this country together, so it would be foolish of the government to not be investing in the arts as a means to that end.”