When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world, Toronto’s LSK Technologies was perfectly positioned. The company had emerged out of one of the University of Toronto’s accelerators — organizations that foster innovation — and was working on creating a test for the Zika virus that had ravaged South America. It quickly pivoted to produce a rapid COVID-19 test, and was awarded a $500,000 federal grant to develop the technology.

It’s just one of the reasons Toronto is primed to bounce back from the pandemic. In 2020, Toronto companies saw $1.2 billion in investment, and the tech sector alone added 70,000 jobs between 2016 and 2020. Hydrostor has just been contracted to build energy storage facilities in California — the largest nonhydro energy storage project ever built. Maple, a virtual health care company that helps Canadians access care remotely, doubled its staff over this last year and is on track for a $100-million IPO. And fiction platform Wattpad was snapped up by a Korean company for U.S.$600 million. The creative and startup economies are transforming Toronto, and finding significant success along the way.

A City of Entrepreneurs: Building a Supply Chain of Innovation, a recent report conducted by the Innovation Economy Council (IEC) for the City of Toronto that I worked on, provides an in-depth look at the organizations that support these entrepreneurs. Through its survey of 36 innovation hubs — a cross-section of academic, non-academic, City-funded and private institutions across Toronto — and additional interviews, I found a thriving community that helps more than 5,000 startups and creators across a broad spectrum of sectors from biotech to fashion. These organizations support entrepreneurs and creatives to learn how to found a business, target a market, launch and scale. They are, in essence, boot camps for innovators.

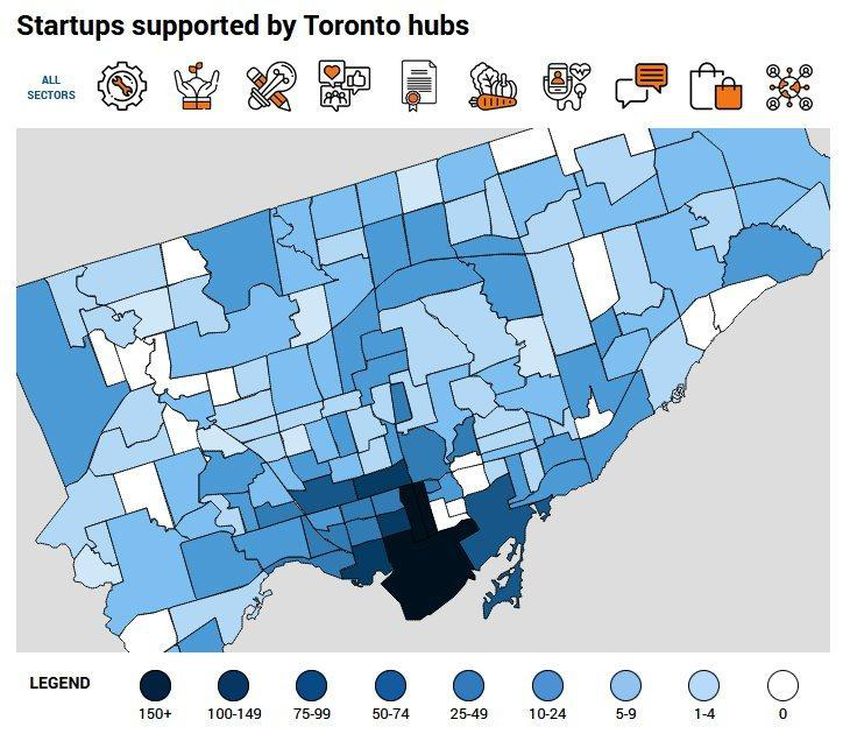

Hubs across the city aren’t just islands, however; together, they form a network of Toronto innovators. The report shows that tech entrepreneurs — particularly those in the software, cleantech and health sectors — are well served by hubs in the downtown core. The density of support that these hubs provide, however, falls off in the inner suburbs, particularly in the northwestern and northeastern corners of the city, which, it should be noted, are among the city’s most economically depressed and demographically diverse. (You can find an interactive version of the map below here.)

As the city emerges from COVID-19, it is an opportune time to reimagine the kinds of help hubs give to innovators. It may also require a rethink of some long-held assumptions.

Krista Jones, vice president of Venture Services at MaRS, points to an often underdiscussed barrier: class. “Innovation is still a rich man’s game,” says Jones. “It’s because of the attitudes around it: you have to have the ability to have a low salary, and you’ve got young people who don’t come from a rich family and who actually need to pay their rent.”

Seemingly simple barriers can prevent people from pursuing their ideas. At the Scadding Court Community Centre, child-minding is a key component of giving newcomers to Canada the time and space they need to build successful businesses. It suggests that in order for Toronto to capitalize on all its potential, we need to support not just the current innovation ecosystem, but the pipeline before it, too.

There are constructive examples. Ryerson’s DMZ runs an intensive summer camp for high school students, and the Creative Destruction Lab at the University of Toronto has a program that fosters entrepreneurship among high school girls. The key is to reach individuals before they make choices as to where to go school, what majors to pursue — but perhaps most importantly, to convince them that starting businesses is something they can do, regardless of where they are from or who they are.

In that vein, Toronto’s innovation ecosystem still has work to do when it comes to diversity. Certainly, the IEC data shows that some strides have been made in terms of racial and gender diversity: based on the information from hubs who collect demographic information, women, Black and POC founders are well-represented. However, there is a tiny number of Indigenous founders and significant effort is required to make Toronto’s innovation sectors look more like the city itself.

But in addition to broadening representation, Toronto could also benefit from drawing on its pre-existing areas of strength. For instance, Toronto famously has world-class medical research facilities, but health and biotech startups represent only 14 per cent of the city’s startups compared to 46 per cent dedicated to digital and mobile media, representing a possible area in which Toronto could capitalize upon the expertise it already has.

There are also emerging global markets in which Toronto could lead. For example, the pandemic has forced food and drink industries to pivot to ghost kitchens, delivery and online storefronts. York University’s YSpace Markham accelerator‚ the first hub dedicated to food and drink is leading the way here. In this and other growing areas like cleantech, green construction and advanced manufacturing, Toronto could take a more aggressive approach in order to lead rather than follow.

As we enter a post-pandemic world, a targeted, strategic approach is the best option to build a resilient, robust economy. From artists and designers to world-leading tech startups, Toronto has the talent to lead — we just need to give people the support they need to capitalize on the strength of their ideas.

Loading…

Loading…Loading…Loading…Loading…Loading…

Disclaimer This content was produced as part of a partnership and therefore it may not meet the standards of impartial or independent journalism.