Support Hyperallergic’s independent arts journalism.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a series on the history of graphic design and social activism in California, with a focus on Los Angeles, published in partnership with KCET Artbound.

The first issue of the Black Panther newspaper hit the Oakland streets in 1967, a four-page mimeograph with typewritten articles and hand-lettered headlines crammed into narrow columns. By the second issue, it had begun its transformation into a professionally printed, expertly laid-out paper with a distinctive, confrontational graphic style. The difference between these issues was Emory Douglas, a talented commercial art student who employed his professional training to provide a unified message for the cause, serving as the Black Panther Party’s Revolutionary Artist and ultimately its Minister of Culture. Within a few years, the influential paper would reach an estimated circulation of around 400,000.

Graphic designers have long played an essential role in political communications, from government ministries disseminating top-down propaganda to radical revolutionaries using their creative abilities to challenge unjust authorities. Beyond simply presenting a text, designers can function as activists, using the arrangement of letters and imagery to build power and stimulate collective action. Douglas’s work played this role in the party, encapsulating its ideologies as they evolved from liberation through armed protest against police brutality to community survival through supportive social programs.

Taking advantage of the newspaper format, Douglas transformed the tabloid-sized covers and centerfolds into inexpensive posters using photomontage, press-on type, pre-printed patterns and economical two-color printing. He used these pages to show a community of Black figures together in the struggle, from boldly drawn, gun-toting men and women to exuberant children to sensitively rendered depictions of daily life in oppressive poverty. While his figures were largely imagined, in his own telling, the images were inspired by his outreach among the people, an opportunity to document lives that were left out of the supposed papers of record. In a stark reversal of conventional media narratives, he uplifted his Black subjects with empathy and dignity while literally de-humanizing the police, who he caricatured as boorish cartoon pigs.

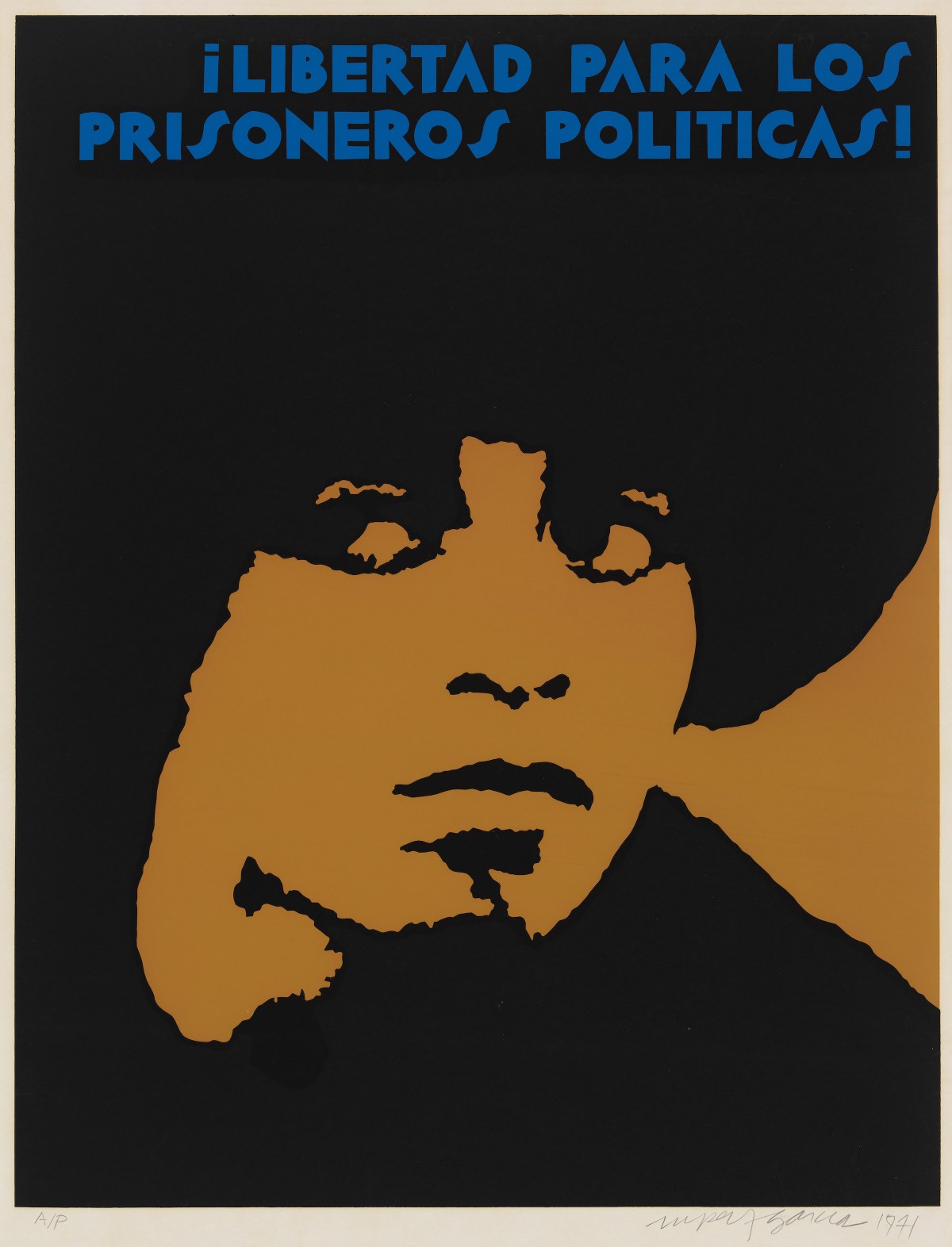

Douglas also used his graphics to express solidarity with other oppressed peoples, and darkened the outlines of his drawings with pen and markers to imitate woodcuts, a medium long used for mass protest and propaganda prints. He studied the revolutionary imagery distributed by the Cuban Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAL), adopting a visual vocabulary of global activism to raise awareness of struggles across what was then called the “Third World.” (The respect was mutual; the Cuban artist Lazaro Abreu enlarged one of Douglas’s illustrations for a 1968 poster.) These exchanges happened closer to home as well. In 1969, Black Panther turned over a portion of several issues to ¡Basta Ya!, a paper dedicated to defending seven Latinx youths (“Los Siete”) falsely accused of killing a police officer during an altercation in San Francisco. Douglas met with artist Yolanda Lopez, whose illustrations for ¡Basta Ya! visually defined the cause, providing insights on how to use newspapers for effective political communication.

As this collaboration suggests, the flowering of grassroots social movements in California in the 1960s and ’70s led to concurrent flourishing of graphic innovation as a form of collective action. In an era when mass dissemination still required printing acumen, progressive print shops put themselves at risk to publish radical outlets, while artists and designers set up workshops to produce large runs of inexpensive posters. The examples are too numerous to list. In Los Angeles, designer Sheila de Bretteville, a co-founder of the Woman’s Building, oversaw a center where women learned letterpress, offset lithography and other technologies that would allow them to find their own voices in print. Chicano artists Malaquias Montoya and Rupert García taught hundreds of student activists at UC Berkeley and San Francisco State College respectively to screenprint, creating a flurry of energetic and often anonymous graphics that animated the anti-Vietnam War and Chicano civil rights movements.

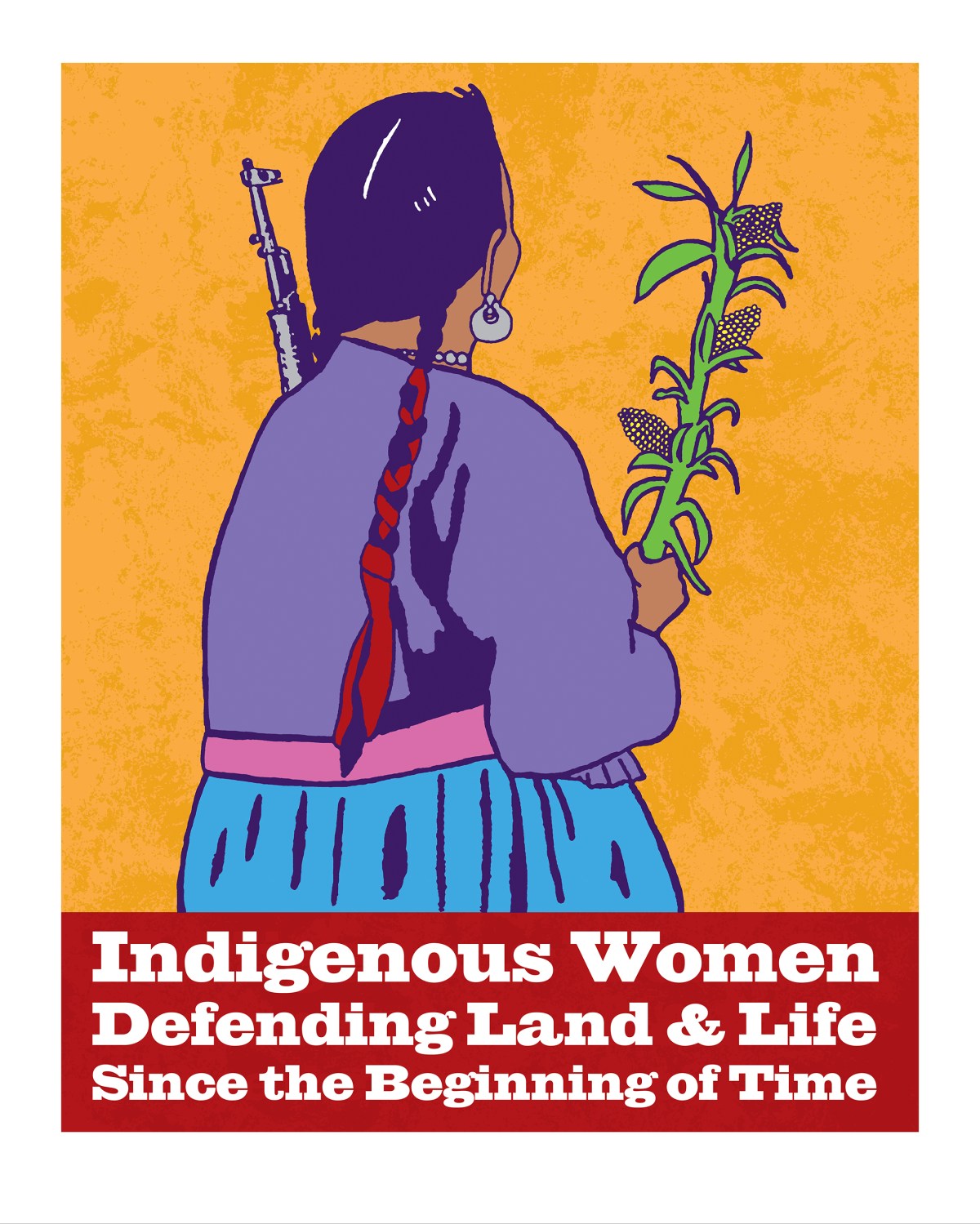

Designers today continue this legacy, using their practices to inspire change and raise up global fights for justice. Jesus Barraza and Melanie Cervantes, the San Leandro artists who form the core of the graphic arts collaboration Dignidad Rebelde, have direct ties to these earlier generations. Cervantes first learned screen printing under the direction of David Bradford, a muralist and printmaker associated with the Black Arts Movement of the 1970s, while Barraza’s mentor Juan Fuentes, former director of the Mission Grafica at the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts, credits Montoya and García for encouraging his practice. Like its predecessors, Dignidad Rebelde pursues collaboration with other politically engaged artists, both locally and through international networks such as the Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative and the Consejo Grafico Nacional coalition.

Barraza and Cervantes’s artistic practice and activist work are deeply intertwined. After Oscar Grant was murdered by a police officer at Fruitvale Station in 2009, they were among several artists who answered a call from the East Side Arts Alliance to raise awareness. With so much anger in the community, they recognized that they could not produce enough prints and instead shared their portrait of Grant for free online. The graphic, which connected Grant’s murder by the state to the simultaneous bombing by the Israeli government in Gaza, circulated widely on social media. Yet the artists also recall the power of walking through downtown Oakland and seeing printed images of Grant pasted up on the walls and feeling the beginnings of a movement coming together. “Political graphics play a role in public memory,” says Cervantes.

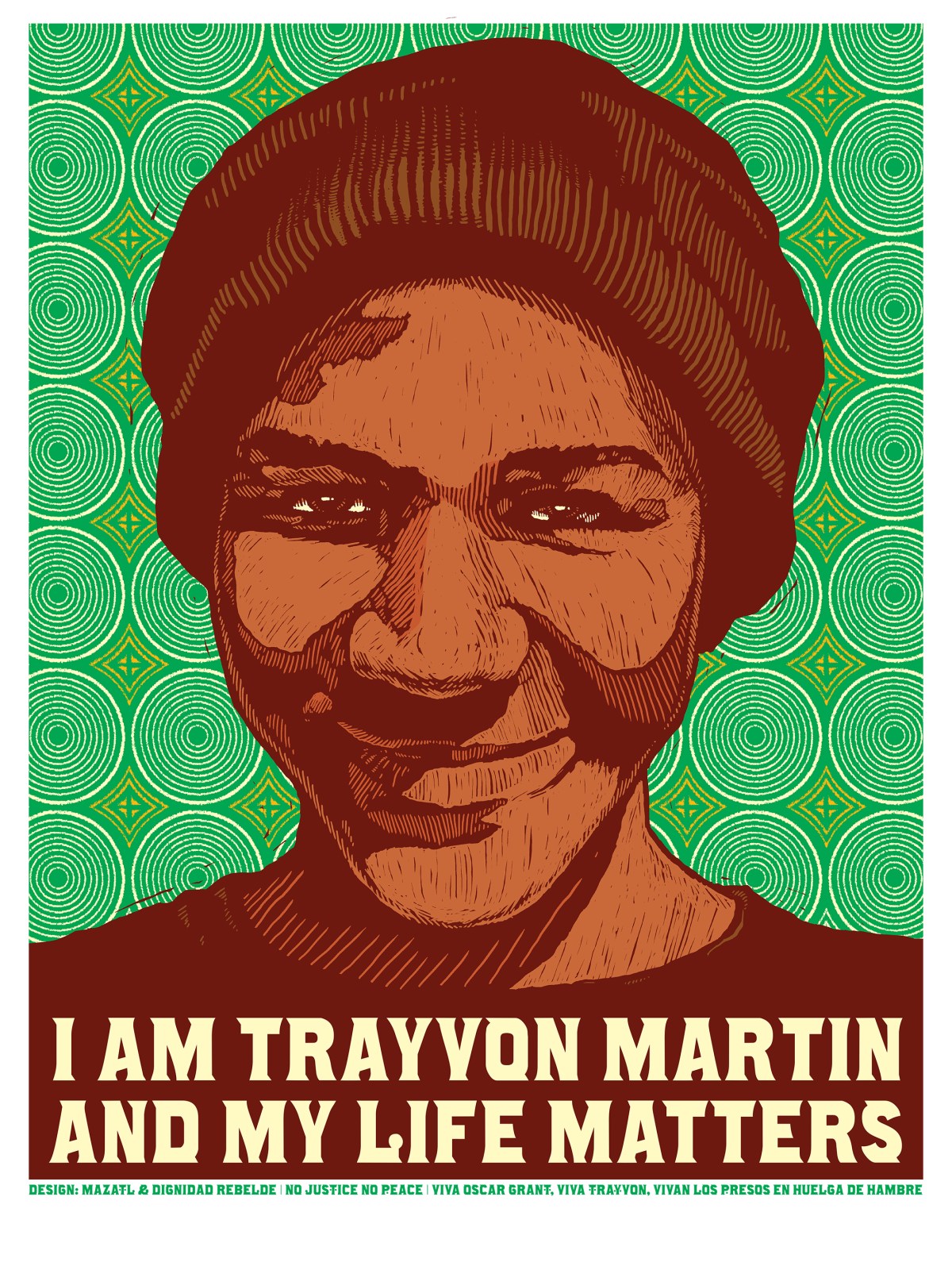

They continue to work in both digital and physical formats, recognizing the significance of both for growing a movement. Their digital graphics circulate around the world, and Cervantes recounts how an image she created in support of uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt was used in a protest in Bangkok the following day. Yet printmaking remains a way to create human connection. They recall a live event, where they invited the public to help print their poster commemorating the life of Trayvon Martin as a collective processing of “an immense amount of grief and rage.”

-

Dignidad Rebelde, “Indigenous Women Defending Land and Life” (image courtesy the artist)

-

Dignidad Rebelde, “I Am Trayvon Martin” (image courtesy the artist)

Dignidad Rebelde’s graphics, like Douglas’s, are populated with portraits and figures, a signal that change happens for and by people. The same is true of Los Angeles artist Ernesto Yerena Montejano. His work has a heroic quality, sun-bathed figures with eyes cast upwards and fists in the air, and faces ringed in sunburst patterns reminiscent of Soviet or Chinese propaganda. Yet his work often portrays real activists, elevating the work of everyday organizing. “We the Resilient,” created for the protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in South Dakota, portrays Lakota Elder Helen Red Feather, a longtime activist in the American Indian Movement. His ubiquitous poster for the 2019 Los Angeles Unified School District teachers strike transformed Roxana Dueñas, a history and ethnic studies teacher at Roosevelt High School in Boyle Heights into an icon, whose face appeared in newspapers and on billboards as well as in the hands of strikers and allies.

Summing up his practice in a 2017 article, Yerena said, “I want to make artwork that’s for something. I’m for dignity. I’m for resilience. I’m for Mother Earth. I’m for honoring elders. I’m for working with my friends. I’m for making positive messages.” Whether the intention is uplift or outrage, designers like Yerena, Douglas, Dignidad Rebelde and many others strive to create graphics that draw attention to causes and campaigns. Yet they do more than simply communicate slogans, acting in the world to strengthen people’s sense of belonging and build real connections, empowering viewers to take action.

You must be logged in to post a comment.